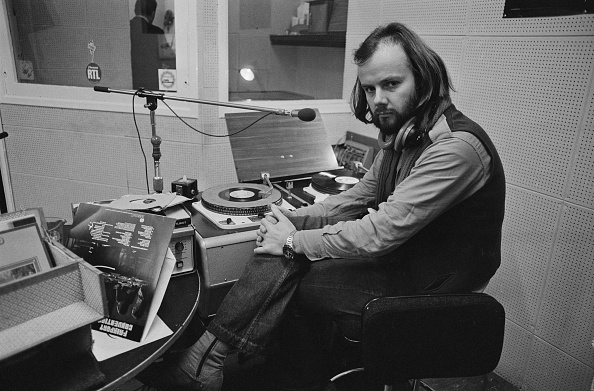

He was a BBC DJ. On the back cover there are heartfelt quotes about him from musicians as diverse as Jack White, Johnny Marr, Elton John, Robert Plant, Nick Cave and Elvis Costello.

He was a BBC DJ. On the back cover there are heartfelt quotes about him from musicians as diverse as Jack White, Johnny Marr, Elton John, Robert Plant, Nick Cave and Elvis Costello.

His name was John Peel.

Here’s a comment about him from Carlton Sandercock, who runs Easy Action Records in the UK:

“John Peel was quite possibly THE most important person on the radio anywhere ever ... to find a DJ that championed new bands, unsigned bands, punk bands, bands of every genre…and encouraged growth when he was employed by one of the biggest corporations in UK is staggering to say the very least … I never met him but did have him stamping on the floor trying to get me, Annie Nightingale and Nikki Sudden to shut up…

“There has never been, nor will be again, anyone else like John Peel … radio stations simply won’t allow it...many, many British acts owe John Peel big style.”

“Good Night and Good Riddance” is full of examples of how, because Peel played either one song by a band or because he played a band a lot, that millions became besotted. Carlton himself named his label after a song by T. Rex who, as Tyrannosaurus Rex, Peel played frequently, leading to their eventual breakthrough and subsequent impact on so many others. I won’t provide a list but when you realise that Peel was the first radio DJ to get excited by David Bowie, Roxy Music, Mike Oldfield, you realise that his impact on the world as we know it was incomparably vast.

Peel had an uncanny talent for … ah, let author David Cavanagh say it:

“Peel’s Zelig-like knack of being in attendance at news-making events - the Oz trial in 1971; the world-exclusive first unveiling of Sgt Pepper in 1967; the press conference in Dallas before the shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald in 1963 - had led him to the site of a major disaster that would be described as European football’s darkest hour.”

That’s not to say there aren’t a few flaws here. If I found fault with this book, you certainly will. But … you and I would have both found fault with, I suspect, almost every single John Peel radio show, so this book is a top-notch, essential purchase.

If I were to give the game away about all the extraordinary talents Peel played when no-one else would, and which of those are now not merely pop stars or household names, but people who genuinely helped shift the world on its axis, you’d be displeased. Instead, we are treated to Cavanagh’s constantly entertaining descriptions of songs or moments which you blink at, then bellow with laughter. I lost it twice during the introduction, hee-hawing and spluttering and quite putting my fellow commuters off their games of flashing lights on their tiny screens. Mind you, perhaps I should’ve brought a hanky instead of using that chap’s sleeve, but never mind.

There are plenty of other moments where I cackle immoderately, which means that you’re churning through this tome of a thing like a rat through a particularly smelly cheese.

Cavanagh sets the book up chronologically, and trawls us through snapshots of Peel’s entire recorded radio shows, taking selected shows and placing them in several contexts so that we get a clearer idea of the DJ in his box in the dead of night, yet at the tiny point of musical advancement and foolishness and innocence.

Like the shows themselves, “Good Night and Good Riddance” is a journey of discovery; you’ll find yourself remembering bands whose names you’d almost forgotten, and never heard, and find that you really must locate them. As a direct result of Cavanagh’s books, vinyl junkies and music nuts the world over will melt their credit cards.

Peel himself had such broad taste, which constantly altered, was never fixed in the way that your standard ‘pop’ DJ still is, that you could be forgiven for thinking him a little mad. The truth is that the BBC found it hard to accommodate him, yet had to. He became enormously important to such a significantly large part of the population, that to lose him to another broadcaster would severely dent the Beeb’s credibility. I mean, here’s a man who played the entire first side (comprising a single song) of an unknown man’s new LP from a relatively unknown new label when such a concept was frankly mad. That’s 25 minutes. “Tubular Bells” caught on quite rapidly after that, with the fortunes of Oldfield, but more notably, Richard Branson, well and truly made.

Peel himself had such broad taste, which constantly altered, was never fixed in the way that your standard ‘pop’ DJ still is, that you could be forgiven for thinking him a little mad. The truth is that the BBC found it hard to accommodate him, yet had to. He became enormously important to such a significantly large part of the population, that to lose him to another broadcaster would severely dent the Beeb’s credibility. I mean, here’s a man who played the entire first side (comprising a single song) of an unknown man’s new LP from a relatively unknown new label when such a concept was frankly mad. That’s 25 minutes. “Tubular Bells” caught on quite rapidly after that, with the fortunes of Oldfield, but more notably, Richard Branson, well and truly made.

At the other end of the scale, a friend of mine was in UK over Christmas ’79, and recalls hearing “Krautrock”, by Faust, for the first time. In the context of all the rellies suddenly turning and squinting, as if to hear better, to the extraordinary noise emanating from the radio, Faust became even more so… particularly as, you guessed it, you were hardly likely to hear anything remotely like this on any radio station in the UK. I heard about twenty seconds of the same song a few months later and immediately slapped the money down. I played it to my friend, “Oh yeah, I remember hearing that in Manchester. On the radio.”

Bastard.

Peel’s breadth didn’t just include Australians like Nick Cave. Dead Can Dance, the Moodists, the Scientists, Hunters and Collectors, Died Pretty, the New Christs and the Sacred Cowboys (among others) all got an airing in the early ‘80s. No-one else was playing them initially …

Peel’s taste was by no means perfect; he never played the New York Dolls when they were around, for example, because he thought they were over-rated. Peel also got over-excited over bands I can’t type without getting a nasty case of the dry heaves, but his saving grace was that you found yourself hearing something which you’d likely never heard before because he was the only dj daft or eccentric enough to play it.

From being an idealistic and outspoken hippy, Peel developed into a sort of backstage genius who showed the BBC what was and what was not acceptable to the wider audience … strange that this fairly quiet individual should be closer to the untapped possibilities of England than the giant corporation (BBC is a corporation, that’s what the C stands for; and no “BBC” has never stood for Big Bastard Clods) with its thousands upon thousands of employees.

For Peel, it always came down to the song, not the politics, not the sex of the artist, not the genre. I mean, the bugger played acid house as it was developing, and never really enjoyed a band called Felt - who were certainly no worse than some of the bands he played frequently. What drove Peel’s taste was ‘as random as a lottery’, Cavanagh asserts and, while I’m sure Peel would have disagreed, to the outsider listening in, Cavanagh nails it.

Of course, there are a few books out already on Peel, including an autobiography and a novel by Peel himself, and while Ken Garne’s “The Peel Sessions” (2008) is also essential as it details a certain period using the BBC sessions which Peel played in addition to records and tapes, “Goodnight and Good Riddance” reveals Peel as he really was, and the problems which beset him, crammed into his bolt-hole and trying to change the world a fraction at a time. That he was a catalyst for so much change beggars belief.

Just to give you a little extra breadth, I’ve asked a few people who had the good fortune to either record for or met Peel, to share a little of that with us.

Graham Lewis (Wire): “I was an avid fan of John's show from 69-70, and became even more of a fan after seeing him MC a concert at the City Hall, Newcastle of Chicken Shack (Christine McVie), Spooky Tooth … it's fair to say I did a fairly decent impersonation thereafter … Over the years his show introduced me to The Last Poets, Pink Floyd, Beefheart, The Faces, early 70s German music, Roxy Music, Kevin Ayres … and a myriad more of African, Jamaican musics.

“When I went to art school and started DJing, working as a production assistant and later Social Secretary, my following of his show became less because of competing schedules! However, whenever I did listen John's reassuring rumble would pull me in ...

“When Wire were recording “Pink Flag” at Advision Studios off Great Portland Street, Bruce and I would go for a lunch-time pint at the pub which turned out to be the two John's (Peel and Walters) regular, they were a formidable sarcastic comedic tag team and I loved every lunchtime I spent in their knowledgeable company. I thought Walters thought us too clever for our own good … but we did sessions regularly over the years for each new release … I think the last (around “SEND”) was 2002 ...”.

Wire of course came to light around the furore over punk in the UK in 1977 and the band have been making music - that is, entire LPs of music you actually want to listen to and engage with, unlike many of those from that period - ever since.

Let’s hear from someone else with a different breadth of music experience who also lived where Peel broadcast every week.

Gus Ironside (editor of Sogo magazine, writes for websites Louder Than War, I-94 Bar and Vive le Rock): “I'm not sure when I first heard the John Peel Show; it must have been circa 1985. Peel was as much a part of the fabric of life for young British music-heads in in the '80s as Doctor Marten's boots, utilitarian Army & Navy clothing, and opposition to Margaret Thatcher's Tory government.

“At that time, Peel was heavily into the Cocteau Twins, thrash metal, super-heavy dub reggae and art-damage post-punk. I certainly didn't like everything he played, but listening to the programme stretched and challenged me. I heard music I would never otherwise have sought out. Thrillingly clunky hip-hop, Zimbabwean jit-jive and feral art-punk of the Scratch Acid variety - this was neither mainstream pop nor trad rock, though some 'Peel bands' made the transition.”

In addition to Peel's winningly downbeat radio persona, it was the sessions recorded by invited bands that made the show unmissable. Some of these actually trumped the group’s own official recordings; Peter Perrett, for example, has stated that The Only Ones' “Peel Sessions” album is their best LP, and he's probably right.

A hip priest to legions of music fans, Peel's influence is hard to overstate.

As a fan of both The Fall and The Birthday Party, I have to say that their Peel Sessions comprise a series of invaluable snapshots into their development, but also, in context, gave the fans who were champing at the bit for the new releases, a chance to hear the band ‘in the raw’, so to speak. While many artists then felt they didn’t require Peel’s show to ‘break them in’ to a wider audience (after all, having reached the dizzy heights of fame, to return would perhaps be taking away the chance for a lesser-known outfit to shine), many held precarious positions and returned time and again, communing with their wider audience.

Bob Short (Blood and Roses in the early ‘80s): “If you weren't out at a show, you listened to Peel. That was the rule. Now, that didn't mean you liked everything he played. He didn't play greatest hits. He played new stuff from around the world. His taste was broad. He'd play African football songs, experimental noise and dub reggae. If you thought you'd be listening to two hours a night of indie punk, the laugh was on you.

“The thing was, Peel sounded passionate about what he played and just talked about the normal dumb shit from his life like some weird old uncle. He was the very fabric of what many thought made Britain great - that friendly eccentricity. So, when you heard yourself on his show and he talked about your band, I guess you just found yourself being part of something bigger, and you felt that what you did mattered.”

Peel’s impact on the radio was instant; I heard him myself during late 1978. It was quite an extraordinary experience. In context with all the drab grey everyday English entertainment on telly and radio, his show must have seemed like a beacon for malcontents everywhere; Good Night and Good Riddance demonstrates the constant ebb and flow of creative inspiration in a social and political context, which, in my experience, is quite unique.

Jeremy Gluck (The Barracudas): “My foremost memory of John Peel has to be hearing The Barracudas on the radio for the first time on his show. ‘I Want My Woody Back’, our first single, was riding high in the Indie Chart (man, does that bring it all back) and he played it after a somewhat bemused and begrudging introduction that inferred his dismissive attitude to what he must have considered its shallow ilk. Hearing your band on the radio the first time is a solid high in any domain, but having our debut graced by the sanguine Peel doubles its value. At that time I did listen to Peel regularly, but to some extent didn't like or relate to a lot of what he played.

“However, some years later I collated an album of obscure American independent reprobates onto an album entitled 'Beautiful Happiness’ for SOUNDS, where I was freelancing. Peel was plugging some of its artists (sic?) and I duly rolled up to the old BBC HQ in Portland Square to interview The Great One about these bands and his persistent bent for championing the US under(dog)ground.

“Peel monotonally explained his love for them, and how he lovingly tended to the piles of incoming vinyl to find the gems that he would play by long lost scions of crud such as Iowa Beef Experience and art Phag. It was a short meeting, but memorable. Even in Britain, where pirate radio had by the time of his own DJ heyday already created many legends in the trade, Peel was unique in every way, from voice to choice.”

I won’t wax lyrical on Jeremy Gluck’s career post-Barracudas except to say that, like Graham Lewis, their music is powerful and moving and well worth discovering. In many ways - and Cavanagh alludes to this - Peel’s eclecticism encouraged thousands of musicians to ‘think outside the box’, to learn freedom of expression beyond cliches and music for music’s sake (again, I can’t name those dreadful so-serious tummybutton gazers without the heaves … I mean, he once devoted an entire show to Robin Trower).

Cavanagh doesn’t elaborate on the selection process, but it seems to have been osmotic between “the two Johns”, Walters and Peel.

Bob Short: “Peel himself didn't have as much say in the process of getting a session. Peel's producer, John Walters, seemed to be the guy who did the hiring. He also did a Weekly BBC review of the music papers, so he was the guy with his finger on the pulse. Peel didn't come down to the sessions. He lived in Norwich and came down to the show about 10 minutes before he went to air. I know this because, when Blood and Roses made our first demo, Lisa and I staked out the BBC all day to press a tape into his hand. We didn't immediately get a call back. But as soon as the press started, we were tracked down to our squats.

“The sessions themselves were amazing clean scientific things. Rhythm Guitar, Bass and Drums live. Overdub vocals lead piano and - in our case - a hubcap we borrowed from the street outside. I spotted a celeste and asked if I could use that. Within thirty seconds an army of men had dragged it in, mic-ed it up and returned to the tea room from whence they came.”

There you go, fans, John Peel set the paparazzi onto Bob Short. Of course, in devouring this book (it’s just over 600 pages and you get the feeling Cavanagh could cheerfully have pulled out every single episode and made pertinent, entertaining comments) there are two things you want, and the first is to discover a bit more about the man.

Graham Lewis: “After Wire froze in 1980, I'd occasionally meet with John before his show and share a bottle of white. An invitation arrived for Dome to visit Maida Vale on the release of “II ….” Wire's 15 min track/ session of “Crazy About Love” had caused both Johns to think we were taking the piss, a view expressed before playing it. However, true to form, when requests came in to re-air the session, John did!

Nina Antonia (author): “In the early 1990’s, Mojo ran a short lived complimentary publication which looked at what people collected and why. I was asked if I wanted to interview John Peel’s wife, Sheila, about what it was like sharing hearth and home with her hubby’s massive record collection. John’s vinyl library was allegedly one of the largest and best in the world. I’d never been a Peel aficionado, mainly because he had a beard, sat about in muddy fields and whilst he’d championed Tyrannosaurus Rex, the New York Dolls had never been his bag. Culturally we inhabited different planets although he did play The Heartbreakers [and The Only Ones - RB].

“As a youngster, I’d grown up reading his weekly column in Sounds and that too left me nonplussed as I had no interest in the banter about schoolgirls or the occasionally derogatory comments about his wife whom he called ‘The Pig’. Save for the references to music, the column was no different than the bluff chat one might hear in a pub or at a university social; a lad to lad exclusivity … despite this however, the prospect of interviewing Mrs P was appealing. To paraphrase Morrissey, it was time for Sheila to take a bow.

“Almost immediately after accepting the assignment, John Peel called. It was so strange to hear his voice on the phone; familiar and yet unknown. He was concerned. Sheila, he explained, was recovering from a stroke and was not at her best. At once I was struck by how protective he was of his wife and assured him that I would forward any copy to them for approval, before publication. [Note: journos rarely do this sort of thing in the UK, where many journos rejoice in their nickname of ‘the scum’ - RB].

“The Peels lived about two hours outside of London in the remotest corner of a county village. The setting was rustic, their cottage a perfect post-hippy idyll, complete with Victorian china pigs here and there. Sheila was self-effacing but very friendly. As she made tea, John offered to show me ‘the collection’. It had been designed not to interfere with the running of the household and if music was his main love, it became very clear that the well-being of his partner was paramount, even if she didn’t have a gate-fold sleeve.

“Not once did he call her ‘The Pig’, and Peel had about him the sense of a man who had finally grown up, apparently the levelling aspect of siring a brood of his own. As far as recollection allows, there was one large room in the middle of the house dedicated to vinyl, from where he had at one time broadcast his show. The turntable was still set up but he had to commute to London on a weekly basis, to which he seemed resigned.

“The majority of the collection, however, was kept outside the house, in little cabins that resembled guest chalets. John’s vinyl library was staggering, from 78’s onwards, he showed me the first single he’d ever got (but can I remember which it was, can I find the article, can I fiddlesticks …)

“The experience was quite overwhelming; thousands upon thousands of discs on custom-built shelving was displayed, but it wasn’t a graveyard, this was music meant to be played, heard and enjoyed. An assistant had been employed to help to put the records in order, not alphabetically but chronologically. We took a few pictures of a bemused Sheila amidst the racks, the beloved discs that were her husband’s life and by proxy, hers. If he would have been lost without his vinyl, he would also have been lost without Sheila. Was reference made to ‘The Pig’? sort of … Peel airily explaining that he had the greatest affection for the little critters.”

The second thing you want to do is discover all this for yourself. Now, Cavanagh is a fiendish fellow, and he clearly expects us to do this, because first, he only tells us the names of the bands Peel plays on any given session and only occasionally the songs, and second, in the introduction he draws our obsessive attention to this site, which you will bookmark and trawl through when you’ve had too much too drink.

One last quote from Cavanagh who, as I may have indicated, nails him I think as well as anyone ever will;

“Peel’s love of radio seems to encompass everything that can make him laugh, ponder, sit bolt upright, relax, daydream, sing his head off, dance around the room, feel like a citizen of his country and feel like a man of the world.”

“Good Night and Good Riddance” is far too large for most folk’s Christmas stocking, so my advice is to buy four, wrap each in brown paper or similar, wrap each with a large amount of bubble wrap, then plunge each into a much larger brown box, packing around with newspaper, and wrap each huge box with dreadfully cheap Krimbo paper and give to four deserving music lovers (much more effective if they all have very different tastes and know each other). Then add too much rich food and drink and sit back and watch the entertainment.

Lastly, apart from awarding maximum points for “Good Night and Good Riddance” despite my own grievances (which is why that link is there of course, you bastard David Cavanagh), I will close with someone (much like Nina Antonia and Bob Short and Graham Lewis above) whose eclecticism and fiercely free intelligence resembles Peel’s.

Jeremy Gluck: “I've twice had the privilege of recording sessions for Dandelion Radio, a Bristol terrestrial aspiring to honour his legacy, and it's good knowing that whatever slight thread runs from ‘Woody’ through that weird compilation to my Carbon Manual and Plastion somehow is strengthened by association with the greatest radio head ever to make the airwaves bleed. Peel, we salute you!”