K: As a fan of your Epitaph albums, I was disappointed to see the way they were promoted (or not promoted).

W: The rock and roll business today is not the rock and roll business of 10 years ago; it's certainly not the rock and roll business of 20 years ago. Today you really have to use every possible way to reach your audience, because you're fighting for air time with television, the Internet, massive sports, video games, Blockbuster, other stuff that's aimed at people with what they call "disposable income." [Laughs] That's a funny expression...like people have money they don't need.

K: If we can go back a coupla years, when you cut that first album ["The Hard Stuff"], did you have any particular idea in mind?

W: Part of the idea was (and continues to be) to connect with my contemporaries, to re-introduce my work to today's listening audience. That was the thinking...and I didn't have a band together; it seemed like a natural. It was a no-brainer. This is part of Brett Gurewitz' genius. He said, "There's a lot of musicians around that would really be happy to work on this record with you," and they were the kind of musicians that I wanted to work with...the more "street-level" musicians, not the slick L.A. session guys. I do not want "Skunk" Baxter on anything I ever do in my life.

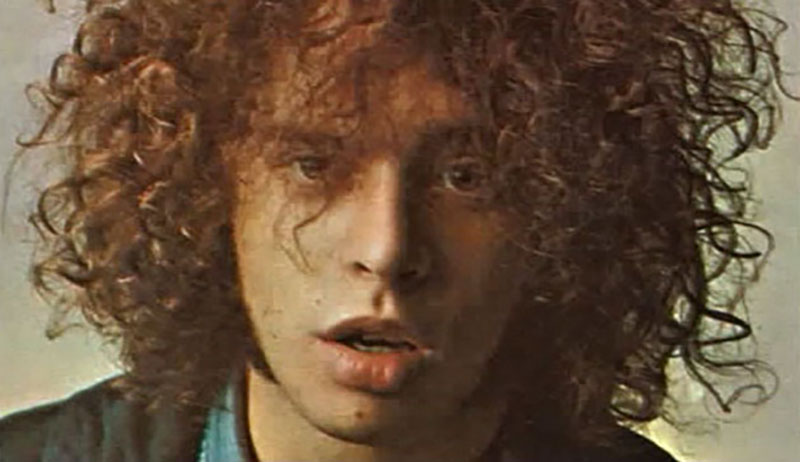

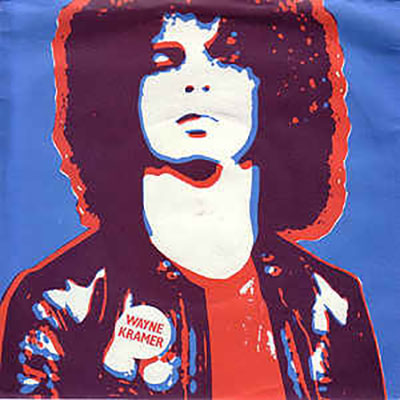

Certainly at the core of the way I look at the work that I do is I'm striving to write songs with meaning, because it's a way to connect, and it's a way to feel like you're having an influence on your community, your neighborhood, your city, your state, your country, the world...mostly on the human level, it's a way to say to people, "You're not alone." It's the life's work. At this point, a lot of what I write is about a life lived. When you're in your late teens and your 20's, you're figuring out who you are, you're kind of unformed, and you're learning how to be you. You're acquiring the knowledge that you're gonna need to be you later. By the time you reach your middle adult period, your 40's, you're kinda filled in, you're not just a blank slate anymore. Now you know, at least you have some handle on who you are in the world. Y'know, I'm 50 at this point, and I'm less uncomfortable with being Wayne Kramer than maybe I was at 20. I'm pretty clear about what my role is and how I fit in the world.

K: How do you envision your audience now? Who are you playing for?

W: I think they are, I'd say, 25 to 45...I think they're a little older, I think they're more mainstream and I think they're serious music fans, people that have grown up. I don't think that they're the archetypal Epitaph audience. Epitaph, I believe, is very into selling punk rock to nine to 15-year-old white suburban boys. Although I think those guys would appreciate what I'm doing, I'm not sure it's for them.

I think my audience is more a listening audience, and I think it's people that still wanna rock, that still wanna find some heart in their music, something that has some substance to it. 'Cause not everybody turned 30 and pulled over and parked. A lot of people might have kids, they might have a steady job and whatnot, but in their hearts, they wanna rock. I don't mean in the dumb sense, BDR, like metal, I mean even though I think people appreciate Metallica and they look the other way, but really, they're singing about demons and...I don't want to underestimate my audience's intelligence. I don't want to play down to them. I don't want to participate in the dumbing down of America. I want to participate in the idea that thinking can be fun. [Laughs] I mean, my brain is my favorite part of my body.

K: There are a lot of kids who I think would respond to this stuff if they could hear it on the radio.

W: Radio's tough right now. If you've got the money, you can get on the radio.

K: Radio's more reactionary now than it was in the '70s.

W: What they've managed to do is to ghettoize musical taste, by isolating everyone and separating out: "Well, this is adult rock, and this is adult alernative rock, and this is hard rock, well this is rap, well this is urban light, well this is..."...y'know, and what it does, it fragments and compartmentalizes everybody and separates everyone to the point where everything is reduced, instead of it all being part of a larger whole of art and of our culture. It's a bad trend, but I think it's like a pressure cooker, and it'll go along and go along and then it'll explode and something will break through or people, or at least one would like to think that we'd reach a point where we'd say, "Down with mediocrity."

K: Mediocrity sells, that's the problem.

W: Yeah.

K: On "Dangerous Madness", was there any conscious attempt to make things more commercial? A song like "Wild America," say, could really have been a radio hit. "Back to Detroit" is such a cinematic piece.

W: No, there's never been any conscious attempt to make a radio record, or a commercial record, which isn't to say that I don't want to make accessible records, and write songs that people get.

My attitude is that if I write the best songs I can, and I make the most beautiful records that I know how, then, if that'll put me in a league that if I were to get something on the radio, I would be true to what it is that I'm trying to do. I think it would be laughable for me to attempt to make a record that sounds like the Goo Goo Dolls, or even Rage Against the Machine, whom I adore...to attempt to try and make a Matchbox 20 record...I couldn't do that.

But I can make records that, I think, are accessible, that I think have meaning, that rock, that have power, that have a groove, that have wonderful melodies to them. On "Wild America," I was actually trying to write a Motown song.

K: You should've got James Jamerson [the original Motown bassist who played on The Hard Stuff's "Pillar of Fire"] back.

W: The text came out "Wild America" because [co-author] Mick Farren [pictured left] said he'd always wanted to have a lyric that used the word "America" in it. There was no more to it than that.

K: When did you first hook up with Mick [co-writer of many songs on Kramer's albums, whose own "Human Garbage", "Deathray Tapes" and "Eating Jello with a Heated Fork" feature scorching Kramer guitar work]?

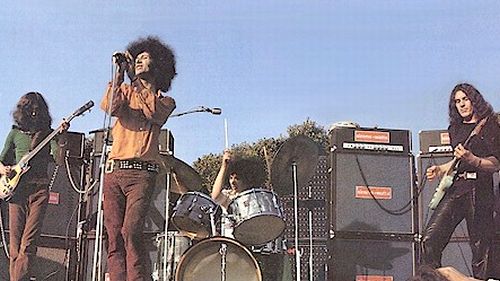

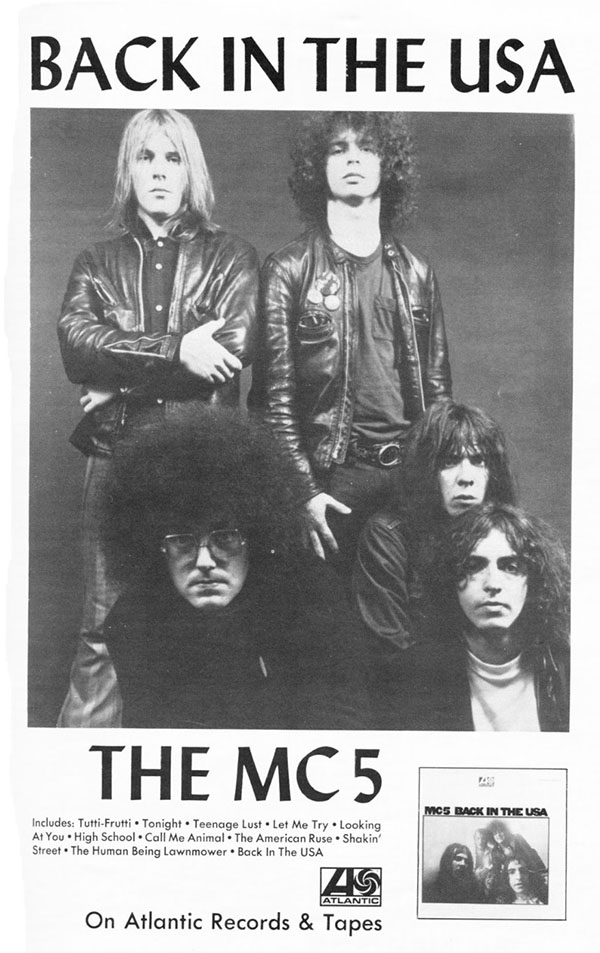

W: Mickey had a band in England, in London, that was kinda parallel to the MC5 [pictured with Kramer playing his stars 'n' stripes guitar] ...they called it the Social Deviants and later just the Deviants, and they kind of adopted the MC5's political stance, they founded a London chapter of the White Panther Party, and about 1970, Mickey was participating in a festival that was called Phun City, and it was kind of like the forerunner of Lollapalooza. It was bands that were kind of outside the mainstream and a lot of booths and William Burroughs was there, and they brought the MC5 over from Detroit to perform. So that's when we met, and we just kind of paralleled spirits, became really good friends. We were interested in most of the same things: drugs, sex, politics, booze...

Mick Farren fronting The Deviants.

Mick Farren fronting The Deviants.

K: I've seen bootlegs of that Phun City show. Is that the first time you went to England?

W: Yeah. It's an awful bootleg. It's completely unendorsed by me. Very bad. In fact, I had to go to some lengths to stop that bootleg. It was a real rip-off. I mean, they were selling it for 40 or 50 bucks with some xeroxes and a T-shirt...really a bad, bad deal for the fans.

Back to Mickey, we've maintained the friendship long-distance over the years, and I would continue to go back to Europe on tour, and he would come to the United States. When I got out of prison at the end of the '70s, I moved to New York and it turned out that we were living blocks from each other, and we started to really pursue our songwriting together.

We actually started right with the breakup of the MC5; he used to send me all the lyric ideas and I would compose a song around it, put a melody on it, send it back, and see if we could interest anyone in making Wayne Kramer records.

It evolved over the years, and then when we lived in the same neighborhood in New York, we wrote an avant-garde musical, a rhythm and blues musical called The Last Words of Dutch Schultz that ran for a couple of years, and was great fun. And we continue to write, up to right now...some ideas will come out of things that we're talking about, or something that we find annoying or perversely interesting. I might write a lyric and cut a song, and a year later he'll come up with a variation on that lyric and maybe take the song to a new level. We recycle ideas a lot, just any way we can come up with something good.

K: Was Mick involved in that single of "Ramblin' Rose" you did in England around '78?

K: Was Mick involved in that single of "Ramblin' Rose" you did in England around '78?

W: Yeah. While I was in the penitentiary, he wrote me at one point that all the bands over there were outraged that I had to go to prison and a couple of labels had gotten together -- Stiff Records and Chiswick Records -- and they were gonna put out two of those tracks as a benefit for me, and they were gonna give me all the money when I got out of prison, which was really a brotherly thing for them to do, considering that most people come out of prison with what they have when they go into prison, which is nothing, and that's generally the reason they wind up going back to prison.

But when I came out, I had like 2000 dollars as a cushion to help me adjust to life back on the street. It really, really made the difference for me...not that I would have gone back to dealing drugs or selling stolen TVs or guns or whatever, but it really did...a couple grand, y'know, straightens you out. Takes the pressure off.

K: What about that "Death Tongue" record?

W: "Death Tongue" came out of [Off Broadway stageshow] "The Last Words of Dutch Schultz". At one point, we had this idea of doing a metal record. We made a single for this label in Toronto, indie label. We were kinda happy with the way it came out, and the guy that had the label had a little bit of money, and we discovered drum machines.

We thought, "Oh, man, this is great...it keeps perfect time, it doesn't talk back, it doesn't cause any trouble, you don't have to move any gear, it plays exactly what you want it to play...it's better than a drummer. No pain in the ass drummer!"

We started recording, we had written a bunch of new songs, and John Collins sang most of the material (he was one of the singers in The Last Words of Dutch Schultz and the leader of a pretty popular band in the Lower East Side in the '70s called the Terrorists). But y'know, Death Tongue...the drum machine doesn't wear so well.

When I listen to it now, the drums sound a little static. We didn't know anything about programming. All we knew how to do was figure out a beat and turn it on. It wasn't until later, we were just about done with the record when we learned that you could actually put some soul and some feeling into the drum parts.

K: If we could talk a little bit about that record you made with John Sinclair a couple of years ago ["Full Circle"].

W: Big fun. Well, y'know, John and I have been cool from the '70s. Of course, we had a tremendous bond in the '60s, when John was the manager of the MC5. I had a deep respect and admiration for him.

We had a rough time when he was sentenced to a nine-and-a-half to 10-year prison sentence for the third possession of marijuana. It was a hard time for everybody, and it was especially hard for John Sinclair and Wayne Kramer, because I was the band leader and I was the point man and there was a lot of bad feeling right at that point.

After he was released, he won his case on appeal after serving just over two years on it, and in the meantime I had managed to completely mess my life up and catch a federal drug case myself, and I was locked up for 26 months, and then after I came back from the penitentiary...we were both cool again.

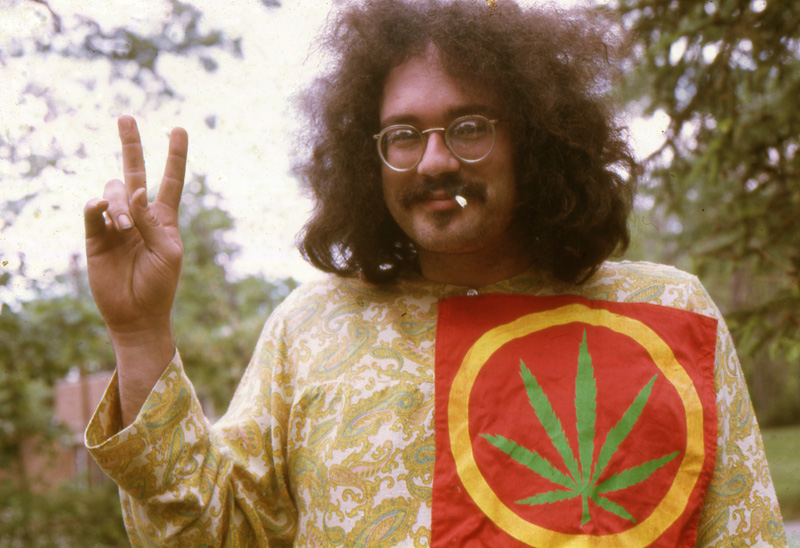

John Sinclair promoting a cause. Leni Sinclair photo.

John Sinclair promoting a cause. Leni Sinclair photo.

I don't wanna say that that's what had to happen, but it was like we had both been through the mill, we had both been scaled and now we were both smooth and we kind of really re-upped, and we started working together back then, back in the '70s, '79, and we've maintained communication all along and conspired on projects.

He would send me a text, and I would take it in the studio and cut a track on it. We did some stuff like that, and finally, he was out here in Los Angeles, and we got Patrick Boissel at Alive Records, who is a real fan, and Patrick had a little money to work with, and we got a chance to make this kind of dream album for us.

And in the meantime, John had been kind of really working on developing his own body of work. He'd written three or four books of poetry, and he had started developing this concept of investigative poetry into the heart of the blues, and the stories of the blues artists, and the roots of the blues, and how it all came to be...and found that he could put it into poetic form, and that the poetic form would indicate the musical form. So the text is set, but the music is kind of open, and it was just so natural to be able to put some musical frameworks around the texts that were connected to the text, that reflected the story line and helped communicate the feeling of the text.

Y'know, there's a lot of what they call "spoken word" going around; sometimes we call it "music and verse," sometimes we just call it a band with John. But it's not just a matter of making beatnik-sounding music and reciting a poem. There's gotta be a connection between what's happening in the text and what's happening in the music, and they both have to be telling the same story. This isn't work for sissies! I mean, this is harder than you'd think it would be -- you don't just make some noise and play behind a poet.

And there's a lot of that; there's a lot of bad poetry and bad spoken word out there. Of course, dealing with John, John is the maestro, and remains one of my mentors and one of my idols. Whatever I can accomplish with the written word, I've learned by studying at the feet of guys like John Sinclair and Mick Farren and Rob Tyner. And Bob Dylan, and Tom Waits, and Van Morrison, and Leonard Cohen. And David Was [producer of "Citizen Wayne", Kramer's "automythological record"].

K: Besides [Charles] Bukowski [subject of the spoken word tribute "So Long Hank" on "Hard Stuff" and "LLMF"], were there any other literary-type influences?

W: Well, of course, William Burroughs....J.G. Ballard, in the early days. Nowadays it's anything and everything I can get my hands on, from Dostoevski to current nonfiction, Elmore Leonard...I'm striving, I'm struggling to write. To be able to get the details out and get a story told. I'm still a student of it. I think I'm way better at it than I've ever been, but I'm even a bigger student. And I think I can do it. I write some stuff every now and then and I think, "Oh, that's not too bad, but then I also write a lot of stuff that ends up in the trashcan.

K: Can we talk a little bit about the Dodge Main shows in Cleveland? (ED: A band with Scott Morgan, Garry Rasmussen, Dennis Thompson and sometimes Deniz Tek.)

W: That was a real rock and roll show. We had done a reading that afternoon at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame from "Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk" by Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain, so that was kind of like the preliminary...the undercard, and then that night we played a show at the Euclid Tavern, which in fact we recorded.

It was very wild. There's an unpretentiousness about crowds in the midwest; they're not hung up about how hip they are. They love this music and they're havin' a ball and they're out in the club and it just makes for a really, really enjoyable night's music. The crowd was so raucous that it was kind of scary gettin' up to the microphone and sing, y'know. 'Cause they kept crashing into the mike stands. This was in a small saloon, this ain't the big time MTV show business with a staff of security guys up front, this is 300 crazed, drunken kids crushed into a little club in Cleveland, so we had to kind of back off the mikes every now and then to avoid getting your lips bashed in with flying FM-58s.

K: Any plans to release the tape?

W: Yes, that'll be out in the New Year. That's on the Muscle Music release schedule. The whole thing about labels is you have to have a release schedule so you can get paid. Distributors will pay you for the current record because they want the next record. I encourage bands to start their own labels and distribute their own shit. Fuck major labels...fuck 'em in the ass. But you have to back up each release with another release. (ED: It remains unreleased.)

Brother Wayne Kramer in the 2000s. Tracey Ketcher photo.

Brother Wayne Kramer in the 2000s. Tracey Ketcher photo.

K: I saw something on the Streetwalkin' Cheetahs website about the Manson Family play you were involved in out in L.A.

W: The Fametti. It's like a story told in photographs. I was [Manson Family victim] Leno LaBianca.

K: How'd you get involved in that?

W: Legs McNeil. He was the connection there, 'cos we shot it at his house.

K: What was that like?

W: It was okay, except for the part where they had to stab me in the chest with a fork, and the fork had to hang out there. The slash marks in my chest that said "WAR." Anything for art.

K: Margaret [Saadi - manager] told me you were writing a TV pilot with George Wendt [the fat guy from Cheers]. Has anything come of that?

W: The wheels turn slowly sometimes in the TV business. It's all alive and well, it's just in kinda suspended animation.

K: Where are you doin' most of your work lately?

W: Wherever they let me. I did a track for a Johnny Cash tribute record; I did a remake of "One Piece At a Time" and I produced a track on the American Indian activist Russell Means, "The Ballad of Ira Hayes."

K: Margaret said you were gonna be making a band with Stewart Copeland from the Police.

W: Stewart Copeland's gonna work with me today and tomorrow on the Brian James record. (ED: Later to be issued as Mad For The Racket.)

K: Who else is involved in that?

W: Duff McKagan from Guns 'n' Roses. Clem Burke from Blondie. We've got superstars coming out the ass.

K: You said Track Records is putting this out in Europe. Do you have an American release planned?

W: No. It might be the first release on Muscle Music.

K: I got that [MC5] "'66 Breakout" thing that you put together for Pat Boissel. Mike Davis [MC5 bassist] told me that was his favorite time in the band.

W: That was the time when it was really pure.

K: What else does Boissel have in the can?

W: He doesn't have anything. These things come out of the air.

K: At the MC5 panel at SXSW, someone remarked that the Five's story is fraught with contradictions, including the fact that you guys were "seduced into the Revolution by wanting to be rock stars." Would you care to comment on that?

W: I think it's the other way around -- we were seduced into being rock stars by being into the Revolution. [Laughs] You can't separate the two. It was a very political time and the MC5 was very much a part of that time. Good art on some level reflects the times around it.

K: What were your best memories of the Five? Mike Davis talked about playing on the boat coming back from Bob-Lo Island in 1965; Dennis Thompson mentioned the Belle Isle Love-In in 1967 (the gig itself, not the ensuing riot) as an occasion when the band just seemed to be hitting on all six.

W: The Phun City festival in London in 1970 was a major high point.

K: What about your worst memories? For Michael, it was being thrown out of the band in England in 1971. For Dennis, it was that last gig at the Grande on December 31, 1972.

W: For me, the worst gig was probably the last European tour that I did with me, [Five guitarist] Fred Smith, a British bass player and a British drummer that we met in the dressing room on the first night of the tour. Some of those gigs were just the worst.

You'd arrive at the venue and the place would be packed. The promoter would be there, and he'd have his family and his children and want to meet everybody, and everyone was all smiles to have the MC5 here from America. The dressing room would be full of fruit and meats and cheeses and flowers and whiskey and wine and beer.

Then we'd go out and play and of course, we were just fuckin' awful. It was just me and Fred and a drummer we hadn't even rehearsed with. He had no idea who we were or what our music was like. Fred and I had never even sung those songs before. We didn't hardly know the lyrics to them, and we'd go out and try to sing these tunes and play these parts. Of course, we were just God fuckin' awful. We'd try to figure out some songs that we could play that everybody would know, y'know, Chuck Berry or Bo Diddley or "Gloria" or something and try to fulfill the contract.

Then of course you'd go back in the dressing room after the show and the flowers and the whiskey and the wine and the cheese and the fruit are all gone, and the promoter's gone, and there's nobody there to pay us. The crowd left the minute you started playing because it was so fuckin' awful. Then you'd have to go do it again tomorrow night -- drive 500 kilometers in the snow to go through it again tomorrow night.

The Scandinavians wanted to sue us because there was no Rob Tyner on the tour, and the Italians cancelled two weeks of dates when they found out it wasn't the whole band...those are some of my favorite memories. [Laughs] Wait'll I tell you about the BAD gigs.

The MC5 in 1969. Kramer at top left.

The MC5 in 1969. Kramer at top left.

K: Back in '96, you told Ken Kelley from Addicted to Noise (defunct website) that the yardstick the Five used to judge your success was historical validation. Do you feel validated?

W: Yeah. We used that lens...was something historically valid, was this gonna hold up? I think the legacy of the Five holds up pretty well. You see it in bands like Rage, and Ani Difranco, and Bono, and Steve Earle, and Bruce Springsteen...Kid Rock; he's a component of the MC5 aesthetic.

K: You mentioned David Was earlier, when you were talking about collaborators and influences. Talk a bit about that relationship.

W: David and I are kind of a two-headed beast that came out west from Detroit. We kind of share an equally twisted world-view of what's going on in music and culture and science and politics, history, art. He's a bro' and he's a mentor and he's a collaborator. He's my dear, dear friend; he's there for me and I'm here for him, that kind of thing. Writing songs together is a real intimate business. Sometimes I'll get asked to be in situations to write with people and it doesn't work, 'cause it IS intimate. David and I have just the best fuckin' time writing songs together because we share so much common ground. It's really one of the biggest rewards of my time now is that I get to collaborate with David Was.

K: Any plans to work together again in the future?

W: Absolutely. We've been working together all along. We've been working on the new Was/Not Was record. I think it's gonna wind up being tied to a film. Some of the tracks will come out in the film soundtrack to kinda reintroduce Was/Not Was to the modern world...to the modern age.

K: "Citizen Wayne" was a cool record not only because it allowed you to tell so much of your story, but you used a lot of different sounds on that record.

W: And there's more to come. We're working on the new Wayne record now.

K: When can we expect to hear it?

W: In the New Year. It's all written now. Y'know how a sculptor looks at a block of stone and says, "There's a great scultpure in there; I just have to trim away the excess."

K: So the material's written. Have you done any tracks?

W: Tracks are done too. As soon as I finish Brian's record, then I'll work on it full-time. 'Cause I work on it all the time. Something comes to me, I write it down, or I'll be sitting at the hard disk, "Let me put this down" -- play the guitar; it's like a big filing cabinet. You just keep filling up files, then when it's time to get ready to do it, you pull it all out and say, "What have we got...let's put this one with that one, and that one with this one, and this one with that one."

K: What musicians are you using?

W: I don't know yet. I'll figure it out as I go along. See who's available. See who's in the neighborhood.

K: What's your current label status? Are you still with Epitaph?

W: I've completed my contractual obligations to Epitaph and we've come to an agreement that my next record will not be on Epitaph.

K: You mentioned a Muscle Music label. How much discussion and work has gone into that?

W: A great deal. It's clearly the way to go.

K: Do you plan to sign other artists as well?

W: I'm more on the Smokey Robinson end of the deal than on the Berry Gordy end of the deal. My interest is mostly in the realm of songwriting and producing. I don't necessarily want to run a label. That's something Margaret can orchestrate.

K: I've been listening to the Streetwalkin' Cheetahs' live CD. I've gotta tell ya, some of the quotes from you I've read comparing them to the MC5 -- I really didn't get it until I heard this thing, particularly the last couple of tracks on the CD and the three tracks on that bonus CD. There really is a strong similarity there to what you guys were doing back in '68.

W: Sons of the Five. That's what I call 'em.

K: You opened some shows in Australia for Radio Birdman back in '96, and you've been touring Europe and America extensively this past year. Any plans to visit Australia again?

W: My bags are packed. I'm ready to go.

K: Any idea what the timing might be?

W: None whatsoever. Haven't really found an Australian promoter that's serious about putting a tour together. The couple of guys that I worked with before haven't followed through. We were talking to a group out there for awhile that seemed to be interested in promoting a tour, but nothing much has materialized. This is something that has to happen on the Australian end. This is not something that I can do from my end. I think the ball is in their court. I'm reasonable.

K: What else have you been up to?

W: We did some work before the last tour started, we shot for a week on the documentary [MC5: A True Testimonial]. Big fun. And very difficult...that's the heavy lifting, to get back in there and try to tell the story of the MC5 with rigorous honesty and still be kind and speak to what the highest ideals of the band were. Regardless of how it may have ended up, and how the combination of the Nixon White House and the conservative music industry ended up crushing the band, the legacy is stronger than ever.

K: You got to talk to one of Rob Tyner's daughters.

W: Just a gift to me.

K: Where are the Future Now folks as far as production goes?

W: I think they've cleared the big hump. Most of the principal photography is done. I think they've got a couple more interviews they want to do, but I think they've got everything they need now. It's the documentary film business; it's always a matter of trying to scrounge up some more money. They've run up their credit cards; they've borrowed from their friends and family...and now they're coming after you!

(ED: The documentary was never released after Wayne Kramer denied the producers rights to the music after a dispute about a soundtrack album. The matter went to litigaiton and the movie was was cleared for a release but bootleg copies of the film had been circulating for years and a commercial release was not financially viable.)

K: I'll have to buy another T-shirt or another hat. It seems like they've made big strides. One more question -- since we're in the I-94 Bar, what do you like to drink?

W: Water. You just can't beat it. And believe, me, I try to pay attention to my precious bodily fluids.

K: It's natural, it's refreshing, and it's free.

FLASHBACK: First posted October 16, 1999: It's been quite an odyssey for Wayne Kramer. From 1964 to 1972, he was point man and Fender guitar terrorist for the legendary MC5, the Ur-American garage band turned psychedelic radicals whose high-energy jams prefigured much of the next 30 years of rock and roll dementia.

FLASHBACK: First posted October 16, 1999: It's been quite an odyssey for Wayne Kramer. From 1964 to 1972, he was point man and Fender guitar terrorist for the legendary MC5, the Ur-American garage band turned psychedelic radicals whose high-energy jams prefigured much of the next 30 years of rock and roll dementia.