Tacttics: Somewhere in Australia.

Tacttics: Somewhere in Australia.

Sydney 1980 was, as Damien Lovelock once said, “as good as anywhere in world at any time for a music scene”. So many bands, so many types of music. By the end of year, I was seeing three bands a week, living on cheap cider at French’s or bumming ciggies from glue sniffers in the Devonshire Street Tunnel. Run-down inner-city share houses made up of like-minded kids from the suburbs, the bush and interstate. Talking about bands, forming bands and attending or playing squat parties.

The Tactics was one of first bands I saw. I’m not sure where maybe French’s Tavern or at the Trade Union in its early days. They played erratic and sharp music, with offbeat reggae feels and up stroke guitars. They still stand as unique. Just like the Laughing Clowns, to this day “nothing fucking sounds like them”.

When I heard that now Europe-based Dave Studdert, the mainstay and creative force of the band, had reformed Tactics for a short Australian tour on the back of a new album, “Early Shift at Charles de Gaulle”, I was damned happy. The last time I saw them play was with The Fall, 30 years ago at some open-air gig in Glebe.

What always made me curious about the band (and whenever I listen to their early records) was how did this band happen? They sprang from Canberra, a city of hipster cool pop stars (and later death metal), that was detached from most o5ther places. How did a band like Tactics emerge there in 1977? I sent Dave some questions. His responses were was what expected – thought-provoking and articulate.

-------------------------------------------

Q There is very much a theory in music that like-minded folk come to the same conclusions in music across the globe at the same time. There was a massive change is music culture in 1977- That said, the Tactics seem to be on their own their planet in, of all places, Canberra. You were angular and modernist. Almost like the architecture of Canberra. Can tell me about the environment and how the band formed?

DS: I’m not convinced by the psychological explanation that begins this question. It may be true, in some parts, but not as much as the operations of power and materiality. In relation to punk, the status of Australia as a colonial outpost of the Anglo-Saxon world always meant that, culturally. It’s generally been subservient to Anglo-Saxon models. These models have one meaning in Britain/USA and another in Australia. Context is King.

In Britain, punk was an act of rebellion. In Australia, in many ways, it was simply a new version of the cultural cringe. Sydney has always been at the forefront of free trade and cultural subservience, but we lived in Canberra - the largest inland city in Australia. There, you saw clearly the inter-relation of the land and white Australia. The green grass of suburban lawns literally stopped in a neat and tidy line at the edge of the suburbs.

We started towards the middle of ‘77 and right from the first we wanted to sound like nothing but ourselves. We didn’t want to sound like punks. We’d heard all those punk records, and the records they copied like the Stooges and the Velvets. They were great records, but we didn’t want to sound like that. We’d have felt like phonies if we had.

All of us wanted something more than what we had. In some ways all of us were a bit lost and were looking for something we could believe in. Anything that sounded like anything else we automatically vetoed it. I couldn’t even play a 12-bar and that was intentional. No one wanted to play blues or play in a blues framework.

I’d grown up in a Western Suburbs meatworks town on the edge of Sydney. I left home when I was 16 and drifted up and down the east coast, doing various jobs. In fact, I’d been travelling ever since I was born so I was constructed as an outsider, and then I became one of my own free will. There’d never been any music when I was growing up. I listened to the radio from 1966-68 but after that I just hung out with the local boys from the meatworks. I’d started reading NME; whenever they’d mention some unknown record, I‘d go and buy it. I learnt a lot that way. I was reading Nietzsche, Reverdy, Vallejo, Mayakovski and Rimbaud mostly. I haunted bookshops, hunting down everything for myself. I was alone a lot and I was angry. Very, very angry.

I did lots of jobs - meatworks, tiling, building service stations, working jackhammers. In Canberra it seemed I went months without talking to anyone. In 1977, I was listening to a lot of reggae and hanging out at the only import record store in Canberra where I got “Forever Changes”, which I loved from day one. It was surreal and misplaced, like Canberra, and sweet and dislocated - like me. I didn’t have much to say. I disliked almost everything I saw of the so-called adult world. At night I’d go out round 2am and drive till the sun came up, back and forth round Canberra, back and forth.

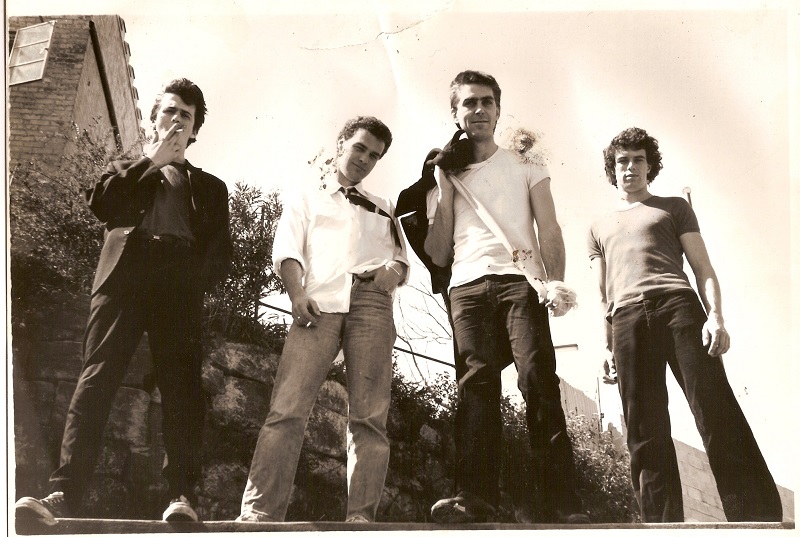

After a while, I met Angus through an ad. He was 17 covered in pimples and with really long hair; a Canberra suburban hipster in love with playing guitar and any drug he could find; he was listening to Robert Fripp a lot. He was crazy but good. I didn’t smoke or drink and was crazy in a different way. We made a perfect pair. I had to sack his mate Terry though, for coming to practice tripping.

Then we found Bob who lived in a house full of free school hippies. They wore bells round their ankles and went around in bare feet. They were still living in 1967 – provincials; who thought Angus was some weird Westie and I was cynical, violent and nasty. It was 1977. They put shit on Bob all the time for practicing with us. Bob wasn’t like them - he was less pretentious, more suburban. I really liked him a lot. Somewhere along the way, I named us Tactics. We used Bob’s garage. There were lots of bass players, no-one special.

We wanted to sound like the bush at night; we wanted to be light and very fast with really strong rhythm. I always felt that if the rhythm was right everything was right, and I worked a lot with Bob to get the drumming really powerful. I want him to play the rhythm not the beat - there’s a big difference; Bob was smart enough to understand. I didn’t really care about bass at all. I wanted the drums and the rhythm guitar to mesh into a kind of machine. That’s why I always loved Bob’s drumming because he was like a human drum machine that swung.

After a bit we got a few gigs and a punk scene started up, straight out of NME. The Thought Criminals came down from Sydney for a punk night in the Uni Refectory. It was before Canberra knew what a punk was – they all turned up in custom (clothing) of their own creation, it was an outburst of creativity and it lasted one whole night. After that they wore black trousers and “official punk gear” from NME.

At the Refectory, they all stood way back at the far end of the room. One of the Thoughties, a certain Greg Sun, crossed the 100 yards of bare floor and eyeballed me; afterwards he told everyone that I was great and the band was shit. For the next three weeks everyone in Canberra told me the same thing.

“Forever Changes” was a great blueprint for us because it mixed different influences into a unique sound and that’s what we wanted to do, but in our own way. We looked at Canberra, this green city in the middle of a brown outback world, with its Spanish suburban houses, its vacuous individualism, its mish-mash of styles, its lack of identity, and we took a lot of inspiration from that.

The lyrics for “Standing by the Window”, written in 1977, were based upon Aboriginal song cycles – where the sentences describe situations without metaphors in simple descriptions which alter slightly, and gradually, over each sentence to build up an entire description. “Buried Country”, I wrote in 1977, and it was clearly about the hidden Australia that no one knew about, or even spoke about much in those days. Seventy-seven was also the year I wrote “National Health” about White Australia, its complacency and arrogance, and “Settlers Complaint”, about the fear and dislocation that whites felt when they first came to Australia; by implication it extended to how people felt in modern Australia.

I was trying not to use standard chord progressions. I wouldn’t write anything in G ‘cause I’d read somewhere that’s what everybody did.

It seemed to us that no one had done what we were doing before. We were trying to awaken people to the country we lived in. We felt that there was a lack of identity, on a personal and national level, and that if we could change the way people saw themselves we could change the political world as well. We were very ambitious and focussed and we all practiced a lot and talked about it a lot. Angus was right up for this, perhaps because like me he’d lived overseas and saw the uniqueness of Australia and how it was denigrated and repressed within White Australia.

By the time we left Canberra, we pretty much had the style worked out. Though of course, we couldn’t play it properly.

Q Can tell about those early gigs and line- ups? The reaction?

DS: The line-up took a while to develop. We had trouble finding bass players. Eventually Bob suggested Geoff Marsh might play bass. Geoff loved Split Enz. He used to sing “I wish I never” all the time, all the time. He wore bingo caller’s jackets to practice and bow ties. His dress-sense wound everybody up - punks and squares. We thought this was funny, and proof of our righteous cause.

Before he could go permanently though, I had to go ‘round his house and talk to his mum. Angus’s dad gave me a talking to too. People seemed to think I knew what I was doing, though I was never sure.

A guy named Dave Browne organised most of the early gigs. I didn’t like him much at the time but now I see what a key role he played and how hard it was, and I admire him very much for doing it. We played various places: pubs like the Ainslie (in Canberra).

There were a few other bands who began to develop. One was called Mixyo, another was a band run by a guy named Karl May. The Suicide squad had started by the time we left. Mostly though I kept my distance. I didn’t think they were serious and I wasn’t interested in the various punk rituals which they assiduously copied - like spitting and one-two-three-four etc etc. We never wanted to be a punk band, wear a uniform or spit on each or anything. We weren’t writing songs that mimicked punk titles about being bored and so on. Everyone was firm about that.

After a while there was this slow, sour blooming of high school bands playing “I Wanna Be Your Dog” really badly and getting all their friends to watch. I didn’t have any friends so I was at a bit of a loss on that score. Anyway, all this meant we slipped down the bills, so finally, it was Sydney or bust.

The reaction was largely disinterested. Some people got what we were trying to do but it was more about friends and having fun and we weren’t really a cartoon band and that alienated others.

Q Around the time of the first up you headed to Sydney; what did you find? Can you tell me about the music culture of Sydney in 1979?

DS: Well there was a bit of a lull at that time. Birdman had broken up and the punk scene was only just starting. We played with the Thought Criminals, who got us gigs, and Voight 465 and that was pretty much the scene.

We played down at the Sussex (Hotel) for a while – three sets on a Saturday afternoon on the floor. There were a lot of venues, though, and every corner pub seemed to have a band. After a bit, Roger Grierson started finding us gigs Three-band bills and the crowds were good at places like The Metropole and various others. At the same time, there were huge sub-Birdman nights with six Detroit bands per night but we stayed away . We weren’t invited but we wouldn’t have gone, anyway, for reasons outlined above.

I’ve written on our website about French’s - that was where it really got going. Roger said he asked the owner 28 times to get a gig. Then it was Rags I wrote about that. Mostly the scene seemed to consist of bands from one of three categories: British punk, Detroit Stooges stuff and European arty noise groups. Everyone fell into one or other of those. On that compilation “Can’t Stop the Noise” you can hear that pretty clearly.

After a bit, everyone started getting a band together we started slipping down the bill. By this stage we were playing at the Stagedoor but only during the week. We seemed to be sliding inexorably to the bottom of the bill, since we didn’t have a lot of art school mates and we were strangers in town. Still, people started turning up early to see us and so on. I didn’t really pay much attention actually.

The scene was very competitive lots of back biting and so on but it drove people on to be better and the level of playing improved rapidly. I recall coming back to Sydney one January after being in the country for Christmas, and we debuted “New York” and “China Watcher”. We kept getting better and better, song-wise and playing-wise, and people seemed to respond to that.

Like I said, I didn’t pay much attention; I was driven by something I couldn’t describe. I never played in a band before. I knew we had something but I didn’t know what, and I was constantly worried if I let go and stopped being so obsessive for a moment, it would all slip away from me.

2JJ was great – back then you could walk in off the street with a single and they’d play it there and then. We did that with “Hole in My Life”. The scene was really healthy and competitive; there were factions arguing over different bands and everyone claiming their’s were the best. It really hummed - as those sort of competitive scenes always do.

Almost all of this stopped round about the time the Trade Union Club opened. There was a marked decline in creativity and energy for new music. It all became much like an RSL club in the suburbs with people dressed different. In any case by then a lot of the early bands - Thoughties, Voight 465, Seems Twice, Sekret Sekret - and so on had broken up. And of course “the business” was buzzing ‘round which altered the vibe markedly. It’s never the bands who are first who make it, they’re far too radical. The ones who are second don’t, either. But the third wave of bands always do and that’s what happened here, and unfortunately they were diluted and rather cartoonish posturers by then.

And though millions will disagree, that’s what I saw.

Q: “My Houdini” stood apart from all the trends of a post-Birdman Sydney. Can tell me your thoughts on the reasons why?

DS: I think I answered that pretty much – we were from an inland town and even by Australian standards, we were isolated. That gave us a chance to do our own thing and not just imitate duplicate and replicate - which is the standard Australian (and particularly Sydney) thing.

Q: Tactics were around in various lines up for decades. What were your observations about how Sydney scene was changing?”

DS: By 1984, most people saw us as redundant and failures. We still drew good crowds in the inner city, but the booking agencies decided that we were never going to make it and barely gave us a gig beyond Enmore. This started just after “My Houdini” came out; indeed the only way we even played on the Northern Beaches was to rent our own halls.

In the entire Tactics time (1979-1986) we played Melbourne exactly three times and Brisbane once. That was it. So as far as we were concerned, we weren’t part of the scene at all. We were like “the underground’s underground’ - we played great gigs and drew good crowds but no one other than the audience and the band gave a shit or paid attention.

Q: Dave you moved to England. Why the shift? What have been the highlights since you moved there?

DS: I was sick of Sydney. By this stage (1987) I was an outcast - or least I felt like one. All around me was a business - and I was excluded. So when we got some good reviews in the UK for “Blue and white Future Whale” and someone offered me a ticket, I thought: Why not?

Musically, the entire time in England was a constant struggle. I made some great records in the 90’s - especially records that have never been released - but although I played, a lot I wasn’t connected enough and was also too preoccupied with surviving to sustain it or make contacts. England is a very sewn-up market and I couldn’t un-stitch it, so I’d have to say some of the gigs with Mumbo Jumbo at The Conspiracy Club, which I started in Soho in 1994, and the records I made - especially the “Ancient Now” record, which I still think is one of the best 2-3 albums I ever made.

Q: How did this new album come about? What sets this apart from previous albums?

DS: What sets it apart is that it’s done in the 21st Century. it still exhibits the style of Tactics but it broadens it, and my singing, I’m especially pleased with. I feel this is the start of something new for me and for the band and there’ll be several records along in the next six months, which hopefully will develop the sound further. I live in France now, which I much prefer to Britain. When I’ve played here with versions of Tactics the response has always been fantastic. I’m putting together a band here and I’m going to tour.

Q: Finally, who’s in Tactics for the upcoming Australian gigs? What are you feeling about the new band and upcoming tour?

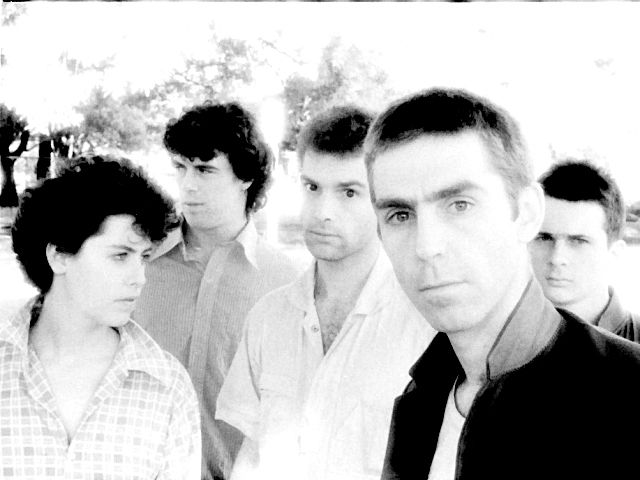

DS: Well, there’s still Ingrid who played on “My Houdini” and “Glebe” and Garry who played on “Glebe” and various other albums like “Billion Dollar Dig” and others, So there’s a consistency there. Lex has also been a pretty regular part of bands I toured with and recorded with over the years. Everyone’s really proud of the record and looking forward to playing some stomping gigs.

As for me, well I feel happier and more creative than I ever have at any time before. I’m making great records, writing shitloads of songs. I’ve found a band in France and a producer in Wayne Connolly who gets what I’m doing and actually makes it better.

Outside of this, I’ve just been given a contract by Palgrave to write a popular paperback on the Gilet. This follows the two academic books I’ve written in the last five years, one of which went into paperback which is rather rare for an academic book. I’m editing special issues of sociological journals devoted exclusively to my ideas, and publishing articles on various topics for the alternative media, both in Europe and the United States.

People are reading what I’m writing and I feel, finally, that the world’s caught up a bit or else re-aligned itself in ways that suit my perspective. After living in approximately 70 places in my life to this point, I have a home and some stability which is also allowing me to go deeper in my work and get down ideas I’ve been carrying around for 30 years, waiting for this opportunity. I feel like the horrible 40 years of Neo-Liberalism is drawing to a close and the world is slowly preparing for new ideas. This is certainly true in Europe, though it may not have reached Australia yet. I’ve got a lot of genuinely new ideas and I feel like it’s absolutely my time.

Tactics will play Marrickville Bowling Club in Sydney on August 9, The Foundry in Brisbane on August 10 and Melbourne’s Curtin Hotel on August 15.

Dave Studdert.

Dave Studdert.