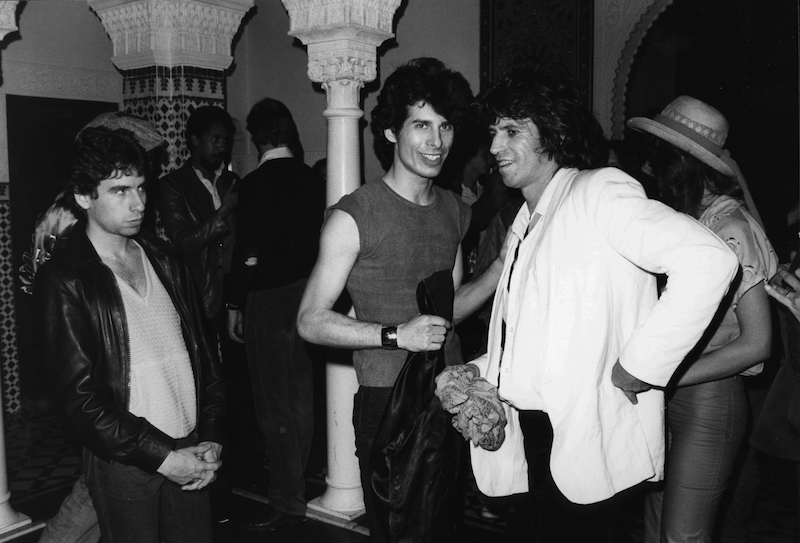

Shaking hands with royalty: Warren Klein with Keith Richards at an after-party for the New Barbarians.

Klein comes with a reference from svengali/star-maker Kim Fowley and something of a professional track record. New York-born and Detroit-based, he was a founding member, lead guitarist, and co-writer in Frank Zappa-sponsored The Factory with Lowell George, who would later to go on to Little Feat.

He’d studied at the feet of folk icon Dave Von Ronk and revelled in the blossoming Sunset Strip scene of the late ‘60s. He’d later study with Ravi Shankar and compose and play music for the montage of stills in Ravi's score for the movie "Charly", play on the soundtrack of “Easy Rider” and collaborate with power-pop maestro Peter Case.

Dubbed Tornado Turner (because Iggy thought he needed a stage-name), Warren embedded himself with the band at their Torreyson Drive house, wrote with Iggy and played a solitary show with the band in Chicago (June 15.) Like one-show keyboardist Bob Scheff (who played the March Detroit show), it was the briefest of “careers”.

Because we’re curious, we tracked down Warren Klein, living in Southern California and still an active musician. He offered a snapshot of Stoogedom and covered many other bases.

Thanks for joining us in the Bar, Warren.

Thanks for joining us in the Bar, Warren.

WK: Thank you for having me.

You’ve had a long and varied career but let’s cut to the chase and start at the middle. How many shows did you play with Iggy and the Stooges in 1973? What do you recall about those gigs and where were they? How soon after did you part ways with the band and how did that come about?

WK: We did one show at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, and I was told beforehand that Mainman was dropping the band after the show, thus no publicist, no pictures, and for me no viable future. The show went really well and Ron ran up to me and gave me a big hug when the show ended, happy it went so well unlike their previous comeback show in Detroit. Since Mainman was no longer in the picture and I was a hired hand to fill in, I assumed that Iggy would get James back in the band, best for everyone, and he did.

What were you doing at the time and what did you know of the Stooges? Their star can’t have been on the rise.

WK: Until I was contacted for the gig I had not heard of the Stooges. I was not in a band at the time, and was intrigued by the image and music of the "Raw Power" record. I liked "Search and Destroy" in particular, especially the choppy guitar part, high energy and really fun to play.

What were you told about your predecessor James Williamson and why or how he’d been moved on?

WK: I was told by Leee Black Childers that Mainman had refused to work with the Stooges any more as long as James was in the band. As to why, Leee said that Mainman had produced a big comeback concert for the Stooges in Detroit, and James apparently was a bit crispy and screwed up some songs badly enough that Iggy had to stop the songs midway and start over.

How did you find your short-lived bandmates? Was it apparent that Iggy and Scott were strung-out at the time?

WK: I really liked all of them, Scott being the nicest. I knew Iggy was on methadone at the time, but I didn’t know about Scott.

Did your short time with the band involve hanging out at the Stooge house in the Hollywood Hills? If so, any recollections?

WK: My audition with Iggy was in a five bedroom house at the top of Mulholland Drive in the Hollywood Hills with a floor-to-ceiling window overlooking the swimming pool. We were going to try writing together, and I started playing a slowed down version of a bottleneck thing from my last band “Lazer”. Iggy asked me to play it over and over as he disappeared into another part of the house.

This went on for about an hour, and as I was wondering if we were ever going to get to it, Iggy showed up dressed for stage, makeup, sarong and all. He went over to the big window and drew a giant heart in red lipstick, and wrote “bleeding heart” across it. Then he began to sing the lyrics he had been writing while I played. I must say that I loved the unexpected theater. We proceeded to write “Wicked Dick from Detroit”. I recently sent an email to Iggy’s manager to see if Pop (in the Stooges we called Iggy “Pop”) might want to finish it since I feel it should be heard, but have had no reply.

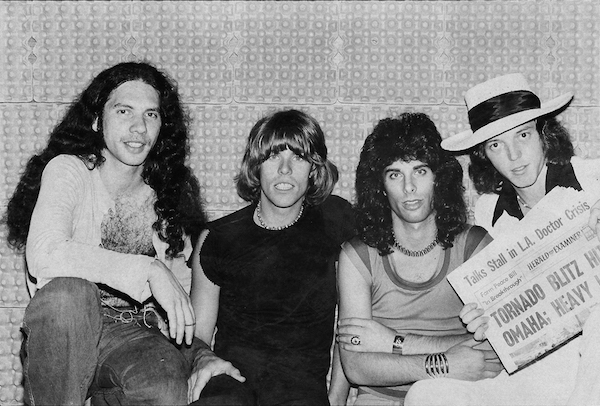

Tornado (second from the right) with his post-Stooges band Tornado.

Tornado (second from the right) with his post-Stooges band Tornado.

Presumably the material you played with the Stooges was from “Raw Power” and nothing earlier? Did the gigs involve much rehearsal or was it a case of being thrown in at the deep end?

WK: Yes, the material we played was from “Raw Power”, and we had a few rehearsals at SIR here in LA. before the concert.

I think you alluded to some new material being worked up at the time. Were these songs you brought or were they written with Iggy? Did they get played live or anywhere near a tape recorder?

WK: I do have a tape of “Wicked Dick from Detroit” with a little blues jam in the middle while we were writing it, but it was not finished. The sound is a little rough with Ron playing bass and me playing guitar through the same little amp.

As an aside, there has been a bootleg recording doing the round for years of Iggy and an uncredited guitarist jamming on things like “Purple Haze”. James Williamson swears blind it’s not him – and it certainly doesn’t sound like his style. Are you able to shed any light?

WK: No, not at all.

Who came up with the name "Tornado Turner" and why?

WK: It was Pop’s idea, he said “I don’t call myself James Osterberg” and wanted me to have a nickname.

The Factory at Fantasy Faire.

The Factory at Fantasy Faire.

Did you have many dealings with the Mainman organisation who were managing the Stooges and Bowie at the time? I’m guessing Lee Black Childers, who was minding them, would have been your point of contact?

WK: Leee worked out of an office in one of the bedrooms at the Mulholland house I described earlier.

Mainman had the band under its thumb at the time and drip-fed it money. Did your gig with the Stooges pay? How did it end?

WK: I gave Mainman a number that I needed in order to play with them since I had rent, bills etc. to take care of, and they paid it. You are correct in the drip feed part, as I later found out they were paying me twice what the other guys were getting. I was not happy about that and neither were they.

You were recommended for the Stooges gig by Kim Fowley, who has become a polarising figure down the years. What’s your verdict and how did you become associated with him?

WK: I can‘t remember how I met Kim, but he was a very interesting fellow, and I agree on the polarizing thing. My group Tornado actually recorded a song he co-wrote called American Nights and as you know he had me play lead guitar on his “I’m Bad” album. He also asked me to be in a band he was putting together called “Hollywood Stars”, a kind of follow up to the Runaways but with guys. I turned it down since I didn’t care that much for the music that the band was to play.

You came to the Stooges gig as a frormer member of The Factory. That band included Lowell George who later went on to Little Feat. How did you become associated?

WK: I met Martin Kibbee, Lowell’s high school pal, up in Berkeley, and he brought me down to LA to meet Lowell. I played “St Louis Tickle” on acoustic guitar for Lowell, and was instantly in the band. Hard to imagine since it was to be a rock/blues band and I had never played electric guitar until then. Lowell put me up on his couch in the tiny house he was renting in Beverly Glen until a larger house was rented in Hollywood for the whole band.

With bandmate in Lazer and The Wolves, Niki Oosterveen.

With bandmate in Lazer and The Wolves, Niki Oosterveen.

Talk about Los Angeles in the mid-‘60s and the scene that centred on The Strip.

WK: The scene in L.A. as well as Berkeley was absolutely outrageous by today’s standards, or any standards for that matter. In Berkeley the proliferation of LSD was astounding. I remember going to a concert featuring Lovin’ Spoonful and drinking the punch, soon to find out it was laced with Owsley’s finest.

In L.A. the Strip was teeming with rock and roll activity. Most rock musicians, myself included, were perpetually at the Rainbow Bar and Grill between 10pm and 2am. I played several of the clubs on the strip, most notably the Whiskey Au Go Go, and played several times there with the Factory along with the Mothers of Invention. Frank Zappa was producing the Factory and his manager Herbie Cohen also managed us. We played the “Freak-out” and “Freak-in” shows with the Mothers at the Shrine Auditorium and the Earl Warren Show Grounds as well as the Whisky. Most fun, though, were solo gigs at Bido Litos, a tiny club in an alley in Hollywood.

I get the impression Lowell George was some sort of trust fund kid. Is that accurate? Did you have anything to do with him in his latter decline?

WK: Lowell and Martin financed the Factory, rent, food, clothing, instruments etc. When Lowell was putting Little Feat together he invited me to play guitar in the band, but I was intent on putting my own band together to play hard rock. He later published a few of my songs, also.

You had a couple of recordings by The Factory produced by Frank Zappa.

WK: Frank produced most of our tracks, and he definately put his stamp on some of the material which we greatly appreciated. Some of those tracks were later released as "Lowell George and the Factory" to capitalize on Lowell's Little Feat fame. Our first producer was Marshall Lieb (Teddy Bears) and with him we did a few tracks with Emil Richards, a legendary percussionist who had an appreciation of odd time signatures as we did.

Can you talk about him and the sort of bands he was working with in the late ‘60s? Did you have much to do with Captain Beefheart or the early Alice Cooper band?

WK: I remember Frank was working with the GTOs, but no other bands were on the bill when we played with the Mothers.

We hung out with Don (Captain Beefheart) occasionally, and witnessed some of his soprano sax bliss close up. I really enjoyed his company and his avant-garde wit.

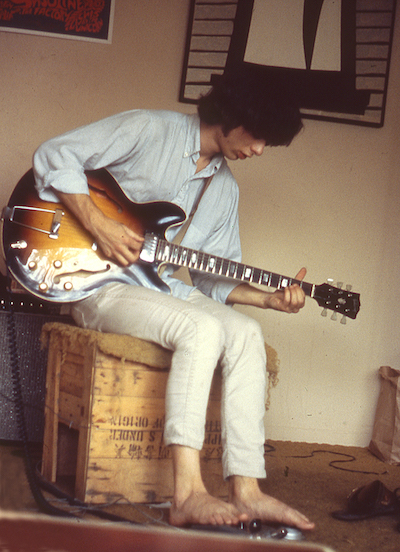

Kicking back at the band house while in The Factory.

Kicking back at the band house while in The Factory.

Tell us more about The Factory and what about those appearances in “F Troop” and “Gomer Pyle USMC”.

WK: "F Troop" was a blast, riding into town on a stagecoach as “The Bedbugs”, only later to have food thrown at us while we played, an odd precursor to the concert with Iggy. Funny thing was, we had to select from a boring list of songs that the studio owned publishing on to play on the show, rather than our own material and ended up playing “Camptown Races”. I believe that video is still available on the Internet.

The Gomer Pyle show thankfully allowed us to play “Candy Cane Madness”, a song co-written by Lowell and me.

You went on to The Fraternity of Man who had a song (“Don't Bogart Me”) on the soundtrack to “Easy Rider”. Was it written specifically for the film? Is that something you dined out on for a while?

WK: Actually, the song title is “Don’t Bogart that Joint”. ABC Dunhill dumbed it down for the mass midget mind. We received very little money from it aside from our initial signing advance with Tom Wilson. I must say that the music business in those days had serious problems, and Tom was a case in point. When we signed with Tom, our attorney suddenly moved from a tiny office in Glendale to a prime spot at Hollywood and Vine. We later found out that he, who was supposed to be looking after us, was being wined and dined by Tom. We immediately went to the lawyer's office and removed our file. Shortly afterward the offlce was vacated and he dissapeared. That sort of thing is a large part of the reason I abandoned music as a career for many years in order to make a more secure living and be able to concentrate on music again in the future.

You worked with Tom Wilson as a producer. What was he like?

WK: Due the bad business with Tom and his partner who managed us, I have nothing nice to say about him other than that he signed us, gave us an advance, and allowed me to hire Taranath Rao, a tabla master brought over by Ravi Shankar who I was studying tabla with at the time. I wanted him to play on my 3 1/2 time solo in “Oh No I Don’t Believe it” on the Fraternity of Man record. The song was written by Frank, but we re-wrote it and added a bridge. We also later performed the song backwards, calling it "On Ho". It was a pain to learn, but caught the attention of free jazz aficionado Buell Neidlinger (Cecil Taylor), and I subsequently performed that backwards version with him and Marty Krystall on sax.

I read you played in a band with Noel Redding. How did that come about, presumably he stayed on in California after the split with Jimi. How was he disposed towards his former bandmate and boss?

WK: Michael Des Barres’ wife Pamela introduced me to Noel. I don’t remember him ever talking about the past, though. He was just the sweetest guy until he started drinking.

You studied Indian classical music and became a disciple of Ravi Shankar at his Kinnara School of Indian Music in Los Angeles. How did that come about and how did that parlay into film and soundtrack work? Was this at the same time as George Harrison? Were there any other notable alumni with you?

WK: In my senior year of high school my family had moved to Westbury New York, and at school I was told I could skip a class if I attended a scholarship offer from the Navy and really wanted to skip the class. This led to me getting a full scholarship at Pratt Institute to study electrical engineering, and it was a work/study thing that had me working in the Naval Applied Science Lab. My boss there played a Ravi Shankar record for me and I was mind-blown.

Fast forward to the Factory, and after hearing that Ravi had started a school in L.A. both Lowell and I headed over there immediately. After two years of study Raviji (Ji is a term of respect in India) accepted me and one other to become his disciples, done in an elaborate ceremony. Some time later he told me he was having trouble composing music for the montage of stills in the movie Charly that he was scoring, and asked me if I could habdle it. Of course I said I could. I brought my then band Fraternity of Man in to play my idea for it, basically me improvising over some chord changes that could sync to the visual, and it was accepted and put in the movie. When we went to the screening of the finished film, the screen credit I was promosed wasn't there, but I felt honored to have done it nontheless.

And yes, George Harrison was around then and I was introduced to him at one of the concerts. He also came to the A&M studio where Ravij was recording his “Festival From India” box set, and sang and played My Sweet Lord that he had just written during a break in the recording.

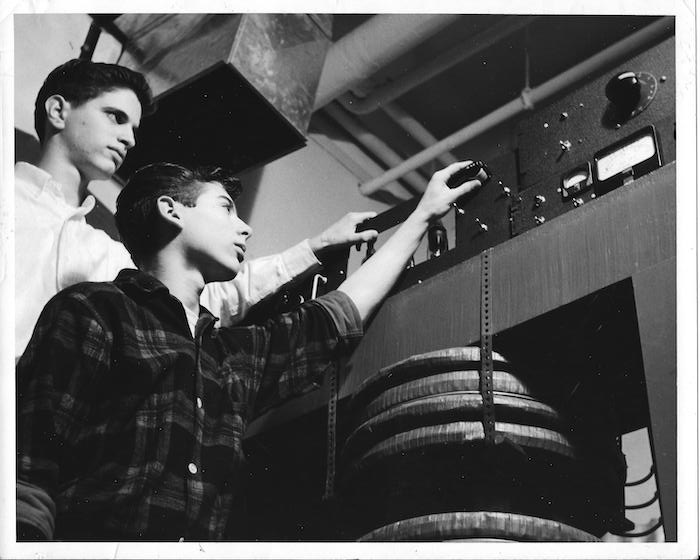

"In my junior year at Berkley High in suburban Detroit we were building a small cyclotron. I was Chairman of the electromics commitee and was tasked with building the associated electronics. In the picture I am adjusting the generator field supply that I built in my basement from a bare chassis & parts. It controlled the 10 kilowatt generator that powered the giant electromagnet in the picture. The electronics were later moved to the control room next door. You would not want to be wearing anything metalic like a watch when that magnet was powered up."

People not there at the time would find it hard to grasp what sort of influence Ravi Shankar had in the late ‘60s. As someone who was on hand to see it, what was that like?

WK: Musically and spiritually I consider East Indian classical music to be unrivalled. One of the great and unique things about it is that it allows up to 90 percent improvisation, and that is why it is frequently compared to jazz. Ali Akbar Khan, whose father taught Ravi also performed locally. I think because he came here first, Ravi was more accepted. I remember being at an Ali Akbar Khan concert at the Greek Theater, and when an absolutely enthralling raga ended I immediately stood up to applaud. WhenI looked around, I was shocked to see that I was the only one standing. Maybe everyone was hypnotised.

Plenty of our Barflies (readers) will be familiar with the output of Peter Case, who you went on to work with. Can you tell us about that part of your career?

WK: I met Peter when he was in the Plimsouls. I did a little writing with him, and was in a group he put together called the” Incredibly Strung Out Band”, a take-off from the name of the Incredible String Band. My instrument in that band was the tipple, a ukulele sized instrument with 10 steel strings that can be heard on some small band jazz from the '30s and '40s. We just wrote a song called “Have You Ever Been in Trouble” that Peter says will be on his next album, and we are working on a few others. He’s touring constantly and lives in San Francisco, so it’s hard to have time to write together. I'm proud to collaborate with him as I consider him to be one of our truly great artists.

That's Warren (right) playing with Peter Case (left) at McCabes in Los Angeles

That's Warren (right) playing with Peter Case (left) at McCabes in Los Angeles

You’ve also amassed many credits for TV and soundtrack work and also Guitar Hero. Is that the direction you consciously took?

WK: After quitting my scholarship at Pratt Institute and hitching to California to play music, doing just that was my mission. But since I only wanted to play a limited genre of music, studio work was not an option to make a living, though I was hired a bit for that anyway. My Wikipedia page has more of those credits.

What’s life like in LA these days and what do you do to keep busy?

WK: Thankfully I am back concentrating on music, and am looking for new song writing collaborators. I have a publisher now that is promoting my music, Red Queen Music. They placed a song from my last band the Wolves (now called Prehistoric Wolves) in "Stranger Things", and they are now releasing music from my old futuristic hard rock band Lazer that is way more guitar oriented.

Skiing has been a frequent entertainment since the snow is so close, and I am about to take up snowboarding as well.

Lastly, since we’re in a bar, what are you drinking?

WK: Most anything non-alcoholic.