James McCann leads his New Vindictives through a set in Sydney.

James McCann leads his New Vindictives through a set in Sydney.

Before he was hanging out with The Drones in Perth, or touring through Europe with his own bands, James McCann cut his teeth playing in a local band in regional Western Australia. It was a baptism of fire, an experience that instilled in McCann a resilience that’s benefited him ever since.

“There’d be bikers, surfers, shearers, hippies, all mixing into one crowd, and fuckin’ getting’ shitfaced,” McCann says. “It could go real good, or it could go south really quickly. Heavy stuff would be happening, and you’d be up there watching. You had to hold your own.

"So by the time we got to Perth, playing was a walk in the park! The whole of my music career since then has been easy, crowd-wise.”

McCann grew up in the Western Australian town of Albany, 400 kilometres south-east of Perth. McCann’s father had moved from Scotland to Australia in the 1950s. After marrying a local woman in Sydney, where McCann’s elder sister was born, the McCanns moved back to Scotland, where James and his younger sister were born.

By 1979 the McCann family had moved back to Australia, settling in Albany where McCann’s father had landed a job with the state government as a physical education instructor. “That was the era of Life Be In It,” McCann explains. “Someone came over to Scotland looking for ideas for that campaign, and offered my dad a job in Western Australia. It just so happened that other members of my family had settled in Perth, so he took the job.”

Albany was, and remains a town centred on farming. Growing up in Albany, McCann observed the motley collection of farmers and itinerant workers and families who cycled through the town. “People come and go, stay a bit, work, have kids, become teenagers, then move into the city,” McCann says.

As he entered his formative teenage years, McCann’s extra-curricular interests began to gravitate toward music, rather than the sporting activities favoured by his father and elder sister.

“My grandfather in Perth, he used to be in a band when he was a young man in Glasgow, called Jack McCann and the Hillbillies,” McCann says. Jack McCann’s band played local dance halls in the 1930s and 1940s. “It was hillbilly music, before Hank Williams, probably more Jimmy Rogers style. Cowboy stuff, violin player, female backing vocalist.”

In the early 1980s Jack McCann still had a collection of musical instruments, including an electrical guitar. One day Jack caught young James hiding underneath his grandfather’s bed trying to work out how to play guitar. “My cousins were playing soccer, running around beating each other up, but I was the introvert, and he knew, I was a red-headed introvert like him,” McCann said.

Jack McCann offered James his acoustic guitar, an electric guitar and an amplifier, on the condition that James learnt how to play the instruments. James had guitar lessons for a few years from a local teacher who’d been a teenager in the 1950s. “He knew all that right hand, rhythmic stuff, like "King of the Road" and "Blueberry Hill". That was a real blessing in disguise.”

By the James he was 13, Jack McCann told his grandson he knew enough to pursue a life in music.

Apart from old blues and country standards, James’ musical knowledge was limited to the pop and rock fare of local AM radio. One day of McCann’s mother’s art students came to the McCann house and started talking to McCann about The Beatles. “We clicked on that, and this dude started telling me about other stuff, like Syd Barrett, Hunters and Collectors, these bands from Perth,” McCann said. McCann’s new musical friend moved back to Perth and began to send McCann tapes recorded off university radio.

A friend of his sister, whose punk-like appearance stood out from the staid Albany crowd, also started to give McCann tapes of more esoteric music: The Clash, Selector, The Specials, The Jam. While McCann found his own way to Radio Birdman, Lobby Loyde, The Triffids and The Scientists, it would be a few years before he realised the artistic and cultural depth of the 1970s Perth punk scene. Bands like MC5 and The Birthday Party were exciting, but initially impenetrable. “Then I realised that it was all just rock’n’roll,” McCann says.

McCann formed his first band in Albany with some friends. The band rehearsed in a local church hall. “We’d be playing Anarchy in the UK, and someone would come in and say ‘If you’re using this space, you can’t sing ‘anti-Christ’. So we’d change it to ‘I’m a naughty boy’ when they were there, then sing the original when they left,” McCann laughs.

By the time he finished high school McCann was unsettled and engaging in standard teenager rebellious behaviour. McCann’s parents paid for McCann to go to Europe “to go away and grow up”. McCann backpacked around Europe, busking to supplement the money his parents had given him.

McCann returned to Australia in the late 1980s and settled in Perth. The rest of McCann’s Albany band, The Raindogs, (including drummer Steve Gibson who would eventually join The Kill Devil Hills, who wrote the Kill Devil Hills’ “Drinkin’ Too Much”), were already living in Perth. McCann moved into a sharehouse with Gibson and formed a new band. “The first time I walked into rehearsal there was blood on the wall - I think Gibbo and Jeff Scott had had a fight,” McCann laughs. “There was always a bit of tension!”

McCann gradually settled into the Perth music scene, playing Detroit-inspired rock at local venues such as the Old Melbourne Hotel. McCann didn’t feel at home in the Perth rock’n’roll scene and decided to chance his hand in 1992. McCann brought with him to Sydney a batch of songs he’d written during a hiatus from live playing. “Before I left Perth I was just hanging around at home, smoking pot, trying all sorts of different tunings. I was sick of all those traditional song structures,” McCann says, “so I inverted all of that”.

Early on his tenure in Sydney McCann formed a band with Tony Robertson (The Hitmen), Murray Shepherd (Hitmen, Screaming Tribesmen) and Murray’s brother Jason. “That was a bit of a joke band,” McCann recalls. “Jason was a real metal head. We were called Blackmosphere. It wasn’t really me!”

Seeing Monroe’s Fur and Lubricated Goat play live in Sydney piqued McCann’s artistic sensibility. McCann also took an interest in “the dark underbelly of the Sydney art scene”, which could be traced back to artists such as Norman Lindsay and the so-called Witch of the Cross, Rosaleen Norton. “That dark Sydney thing was really fascinating for me intellectually. It expanded my whole mind, and I met a whole bunch of really interesting people.”

McCann formed a new band, Harpoon, which featured Melbourne punk alumni (and one-time Beasts of Bourbon candidate) John Murphy on samples. In 1995 McCann also joined Ray Ahn and Peter Black’s post-Hard Ons band, Nunchukka Superfly as that band’s lead vocalist.

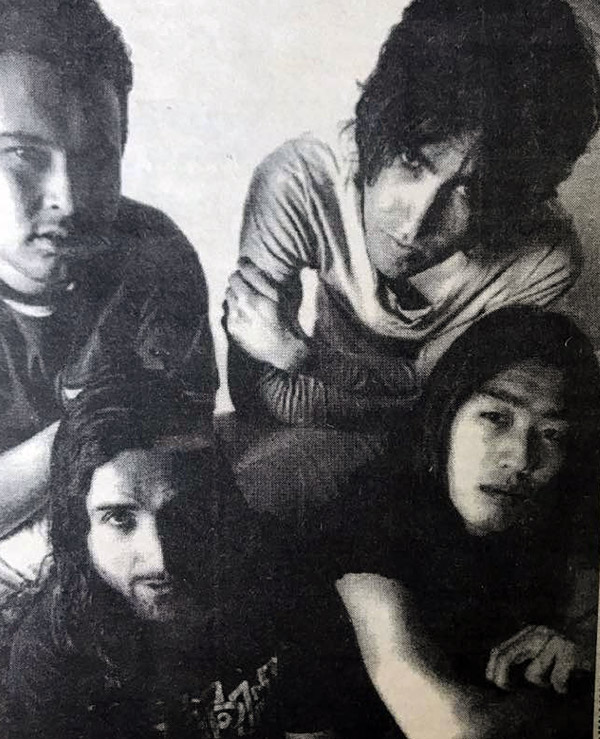

Promo photo of Nunchukka Superfly (from left) Peter Allen, Peter Black, James McCann and Ray Ahn

Promo photo of Nunchukka Superfly (from left) Peter Allen, Peter Black, James McCann and Ray Ahn

“I was the 23rd singer that they’d tried out, and they liked me,” McCann says. An album of Nunchukka Superfly featuring McCann on vocals remains unreleased.

“It’s more hardcore punk pop. It’s a different band from what’s around now. I was half-cooked when it started out, but eventually it locked in. It turned out to be a really amazing band.”

Harpoon began to attract local interest and, surprisingly for McCann, a modicum of media hype. “I’ve got these old clippings saying ‘Harpoon are going to be signed to a major label’,” McCann says. “I’d ring up (promoter) Tim Pittman, and asking him if he’d heard anything, but he hadn’t. It was all bullshit and hype, and I hated that. So I put a halt to that at that time.”

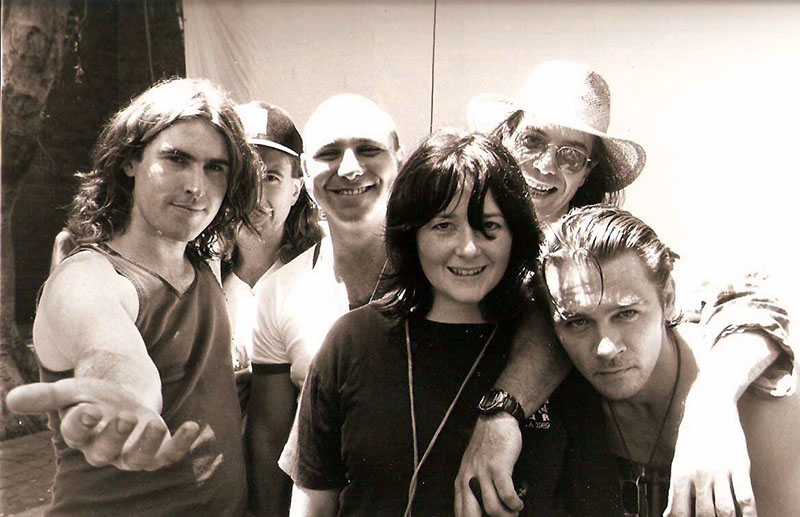

Tim Fagan, Murray Shepherd and James McCann on a Big Day Out stage with Harpoon

Tim Fagan, Murray Shepherd and James McCann on a Big Day Out stage with Harpoon

Around this period McCann had been experimenting with songwriting, creating tighter song structures, and recording a collection of acoustic tracks. “I did about 100 cassettes, which was more first foray into songwriting,” McCann says.

A combination of frustration with specious hype and an artistic epiphany led McCann to the composition of Harpoon and adopt a different stylistic approach. “What I really wanted to do after seeing Monroe’s Fur was to try to do something freer, and a bit more cooperative in a sense,” McCann says.

McCann also had a brief shot in 1993 at joining the New Christs after Rob Younger agreed to audition McCann. McCann reckons he messed up a lead break, but Younger was still impressed enough to ask McCann a couple years later if he was interested in coming to Europe. McCann was excited at the prospect. But when McCann realised he had to stump up the cash for his plane ticket, he realised his chances of joining the New Christs were cruelled.

“I was on the dole and didn’t have any money, so that was the end of that!” McCann says.

Younger, however, remained a supporter of McCann, offering Harpoon a support show not long after. (McCann’s current band, the New Vindictives, supported the New Christs at a show in Sydney in July.)

James (left) with Harpoon

James (left) with Harpoon

Harpoon’s recording career peaked with a seven-track EP on Black Hole Records. Harpoon also scored a slot on the 1997 Big Day Out. Harpoon was in the process of recording a new album when McCann’s elder sister and father both fell seriously ill. McCann packed up and moved back to Perth.

Returning to Perth was emotionally draining. The passing of McCann’s sister and father left an indelible psychological mark on McCann. Unable to leave Perth in the midst of the family tragedy, McCann was compelled to give notice from Nunchukka Superfly.

One night in mid 1997 McCann went to see a former bandmate’s new band, Living Rex. Also in Living Rex was Gareth Liddiard, Rui Pereira and Maurice Flavel. “I saw Gareth and thought ‘Holy shit, this guy’s got something going on’,” McCann says.

A few months later McCann again crossed paths with this intriguing Perth band, now with Warren Hall on drums. This time around McCann got to talking to Liddiard, Pereira and Hall. “They said they had this other band, called The Drones.” Liddiard suggested The Drones could do with another guitarist. McCann said he was interested.

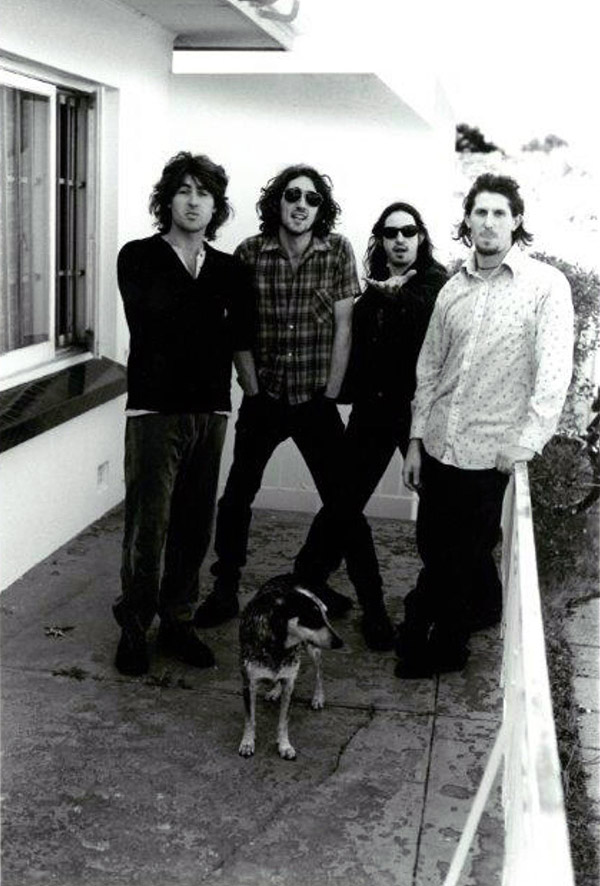

An early Drones line-up with James McCann and Max the dog, pictured in Coolbinia, Perth, in 1999. Darren Clayton photo.

An early Drones line-up with James McCann and Max the dog, pictured in Coolbinia, Perth, in 1999. Darren Clayton photo.

McCann lost contact with Liddiard and Pereira until Christmas Eve 1997, when McCann ran into the pair at the Hyde Park Hotel. Liddiard and Pereira were excited to see McCann and invited him back to their place to listen to some music. Liddiard, Pereira and McCann agreed to meet up again early in the new year. “That was the beginning of The Drones,” McCann says.

The Drones rehearsed in a large house in suburban Perth. “That’s the thing about Perth - you’d have these really big houses where everyone lived and rehearsed,” McCann says. “You’d get really gig quick, and that’s what we did with The Drones”. As well as playing in his own band, James McCann’s Germs (which featured Steve Gibson on congas and a French horn player), McCann also began moonlighting with Liddiard, Pereira and Maurice Flavel in Gutterville Splendour Six.

Like Adelaide and Brisbane, Perth was home to a tight-knit, somewhat incestuous alternative music community. Maurice Flavel was a critical figure in the local scene.

“Maurice was the organiser,” McCann says. Flavel organised a ‘Scum Cabaret Presents’ collective, under which moniker Flavel put on shows for various local bands. McCann and the other members of Gutterville Splendour Six pooled money from Scum Cabaret gigs and bought some recording equipment. Gutterville Splendour Six put down a bunch of tracks at Flavel’s house that were eventually included on the compilation of Gutterville Splendour Six recordings on Bang! Records.

“Gutterville Splendour Six was so heavy,” McCann says. “Sometimes rehearsals could be really tough, but on stage it just turned into this amazing thing”. The Drones had played their first gig in a backyard in Perth. Liddiard, Pereira, McCann and Hall put down a few tracks, each learning something new from the other.

“I was learning how to slow down,” McCann says. “They used to see how slow they could go. I realised later on that they were really influenced by Crime and the City Solution, who I hadn’t heard at that time.” Legendary English DJ John Peel was sufficiently impressed with Gutterville Splendour Six to play one of their songs on his radio show.

In early 1999 McCann moved back to Sydney, followed soon after by Liddiard and Pereira. Liddiard, Pereira, McCann, McCann’s girlfriend and two dogs lived together in a sharehouse in Sydney. Eventually, tension levels in the house rose to boiling point. Liddiard and McCann started arguing and Liddiard, who’d indicated an interest in moving to Melbourne, announced he was moving interstate. Liddiard invited McCann to come too; McCann, still in a relationship, wasn’t free to leave. A few months later McCann got a call from Liddiard, and the pair reconnected.

By this time McCann had formed a new band in Sydney, The Lowdorados, with Mrk Horne on bass (later replaced by Jim Selene) and Peter Booges Werth on drums (followed by Crow’s John Fenton.) The Lowdorados’ set included McCann’s composition “This Time”, which would be included eventually on The Drones’ “Wait Long by the River and the Bodies of Your Victims Will Float By”. Liddiard suggested McCann come down to Melbourne to progress some of his recordings.

Liddiard, who was living in a sharehouse in Baker Street, Richmond, introduced McCann to engineer Aaron Cupples. Tracks from that original Melbourne session at Cupples’ house were released on McCann’s “Where Was I Then” album and the Bang! release “Last Night I Met the Devil”.

By that time The Drones’ line-up had evolved, with Pereira moving from bass and keyboards to guitar, and Brendan Humphries (later of Kill Devil Hills) joining on bass. McCann met Andrew McGee, founder of Greville Records and Shock Records, through Liddiard.

McGee would become one of McCann’s strongest supporters and benefactors, releasing a series of McCann’s albums on McGee’s Torn and Frayed label, including the acoustic “Sweet Casualty” record.

“I went to Andrew’s place with my wife Kate, and he had all this recording gear set up,” McCann says. “I wasn’t rehearsed or anything. I was plied with shiraz, and I put down some acoustic tracks, which Andrew ended up putting out. Andrew was learning how to record, and I was his guinea pig!”

McCann remains ambivalent about “Sweet Casualty”, despite its positive assessment by musicians such as Charles Jenkins and Matt Walker. By the time “Sweet Casualty” was released in 2006, McCann had moved on artistically, forming James McCann’s Dirty Skirt Band with Jeff Hooker on bass, Jo Brockman on guitar and Angus Boyle on drums. McCann also formed a psychedelic jam side project, imaginatively titled James McCann’s Other Band.

James McCann with New Vindictives Jackson Kite (drums) and Chris Taramto (bass). Keith Claringbold photo.

James McCann with New Vindictives Jackson Kite (drums) and Chris Taramto (bass). Keith Claringbold photo.

“It turned into this amazing band with Matt Green on guitar, Simon Edwards on guitar, Jo Brockman, Tim McCormack. It was a thing going on that we could do. We didn’t really rehearse.” McCann also teamed up again with Pereira, who’d recently left The Drones, in Selfish Gene, with McCann’s former Lowdorados band mates Jim Selene and John Fenton and a cast of occasional players, including Andrew McGee.

In artistic terms, Selfish Gene was a return to the expansive approach McCann had taken in the second era of Harpoon. By now McCann had drifted away from his former Drones colleagues, who had generated critical acclaim and national radio airplay with the “Wait Long til the River” album.

James McCann and the Dirty Skirt Band released “Bound for the Blues” in 2006. For McCann, the pinnacle of this particular band came with a show at The Tote. “The show was totally improvised,” McCann says. “It was after a tour to promote the record. Every song was improvised, but it came out like a normal song, two to three minutes.

"We’d gotten so used to playing with each other, we were so tight, and so bored with what we were doing, that we just started making shit up. It was really exciting, and people responded to it.”

James McCann and his trusty Les Paul. Photo by Emmy Etie.

James McCann and his trusty Les Paul. Photo by Emmy Etie.

It was around this time that the seeds of McCann’s European presence were sown. Spencer P Jones had been aware of McCann since Spencer had heard a copy of Harpoon’s mini-album. The Lowdorados also supported Spencer P Jones and the Escape Committee while McCann was still living in Sydney.

“Spencer’s got three different stories of how we met, and they all sound interesting,” McCann laughs.

McCann also remembers playing his composition (and a sometime Drones track) “Sweet Casualty” at a gig in Sydney and looking down and seeing Spencer singing along with the song.

“He must’ve heard it on the first Drones demo that Gaz and Rui gave him. That’s when I got the impression he was interested in helping me.”

McCann subsequently shared a car ride between Sydney and Melbourne with Spencer and his band, during which McCann quizzed the redoubtable rock’n’roll troubadour about his extensive music career and knowledge. McCann briefly moonlighted in Jones’s The Escape Committee when sometime guitarist John Nolan was unavailable to play.

In 2007, Spencer was about to head to Europe with the Beasts of Bourbon and asked McCann if he had any music Spencer could push on European labels. McCann was surprised, and said he didn’t have any finished recordings. “Spencer looked straight at me through squinted eyes and said ‘I just don’t offer to just anyone’,” McCann laughs.

Spanish label Bang! Records was sufficiently impressed with McCann’s half-finished recordings to release “Where Was I Then” (re-titled “Last Night I Met the Devil”). McCann went to Europe on his honeymoon in 2008, and returned with the Dirty Skirt Band the next year on the back of the “Lost Property” EP, a collection of out-takes from the “Bound for the Blues” recording session.

Upon his return to Australia, McCann decided to break up the Dirty Skirt Band and form a new band, the New Vindictives. Eventually the New Vindictives evolved to include Kim Volkman (Love Addicts, X) on bass, Tim Deane on guitar and Helen Buckley on drums.

It was this line-up of James McCann and the New Vindictives that in 2013 recorded the group’s eponymous debut album, produced by Aaron Cupples and released on French label Beast Records. “We were flying by the seat of our pants, but I love that album,” McCann says. “It’s got a great sound, but during the recording it was like ‘Should we go home and rehearse a bit more?’,” McCann laughs.

And then McCann “got jack of everything, the music scene, Australia, Melbourne”. I remind McCann that around this time each time I ran into him in Melbourne he’d proclaim that he was never going to play in Melbourne again. And then I’d see his name listed to play another gig. “I couldn’t help myself!” McCann laughs. “I didn’t know how to say no to when someone offered me a gig”.

After McCann met local musician and producer Dan Sullivan, McCann retreated from live performance and began working with Sullivan in his studio on various projects. One of these projects, a tribute album to Spencer P Jones remains almost, but not quite finished.

“Working in the studio was absolutely deliberate,” McCann says. McCann formed a new line-up of the New Vindictives, with only Tim Deane remaining from the previous incarnation. “That whole five-year period in the studio was so refreshing, to not be part of anything, not to be judged,” McCann says. “I’m in my 40s now, so you’ve got to find other ways of creating, rather than just trying to please people”.

It took two years for McCann and his band to finish the new James McCann and the New Vindictives record, “Gotta Lotta Move - Boom!”, released locally on Off the Hip and on vinyl on Beast Records. McCann has portrayed the intense punk rock edge of the album as a tribute to the Australian rock’n’roll influences of his formative years: Celibate Rifles, Radio Birdman, X, feedtime. A few slower songs were (literally) lost along the way, and McCann resolved to make a punchy, punk rock record.

“I went to America and wrote some songs there, then went and toured France, wrote some more songs there, so I came back with a whole bunch of songs that were faster. If we had done the album six months or a year earlier, it would’ve been a different record.”

In October this year McCann and his New Vindictives return to Europe to play a series of shows in France and Spain to promote the European vinyl release of “Gotta Lotta Move - Boom!”. McCann, who says he’s spent a large part of his career “behind time” - playing songs live after he’s moved on artistically - is pondering whether it’s time to move into a different musical phase.

“I’ve got a whole bunch of songs left over from the last album that I might want to do,” McCann says. “Maybe I’ll stick with the heavy stuff, or maybe I’ll branch out into songwriting again, rather than just riffs.

"The riff-based stuff can be fun, but you can get bored with it. I don’t want to go back to playing acoustic. Or maybe I do,” McCann laughs. “But I don’t want to be remember as just being a country guy!”