Half a Cow in the inner-western suburb of Glebe was the coolest bookshop in Sydney; an advocate of the underground with shelves bulging with left-of-field fanzines, authors who had been banned and musical output from alternative voices.

Half a Cow in the inner-western suburb of Glebe was the coolest bookshop in Sydney; an advocate of the underground with shelves bulging with left-of-field fanzines, authors who had been banned and musical output from alternative voices.

It was a literary anti-establishment. It all came crashing down, in my view, one afternoon in early 1993, during my fortnightly visit to the shop.

A phone call had been made earlier that day and I witnessed the removal of issues of “Lemon” magazine from the shelves.

I asked: “What has Lou done?” and was shown a review of indie-folk pop stars Club Hoy, buried in the back pages.

It was just six words: “These girls deserve a good raping."

"Lemon" magazine was now officially banned. It started one of the most controversial weeks in the history of the modern Australian music industry.

Indeed, it was the flashpoint of the underground openly clashing with the mainstream.

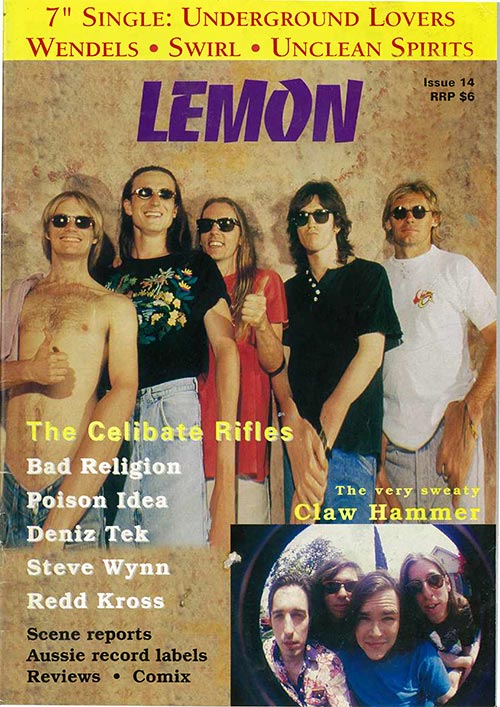

Photo courtesy of Cameron Craig

“Lou” was Louise Dickinson, publisher and editor of the fanzine “Lemon”, which was emerging as a semi –professional publication. It had become the hip, street-level quarterly magazine to read, with a run of 2000 copies. Half were shipped overseas to be distributed by the music super-chain, Tower Records, in the USA. Sealing this deal was a mighty achievement for a 22-year-old publisher and a testament to Lou’s own endeavor and enterprise.

Louise Dickinson was a true individual who was, for a short time, “Queen of the zines”, and a leading advocate for Australian underground music.

A world before we all hooked up online and there was social media and blogs, hard-copy fanzines were the go. They emerged after the Second World War but it was during the punk explosion of the 1970s that they really took hold in the underground music scene.

The outlets to buy them were alternative and indie book and music shops across the globe. Zines were the main way you could read about underground music for, and by, like-minded fans with a street level voice. Zines were the channel via which many people first heard about New York punk, Radio Birdman, Sonic Youth, the Birthday Party or Nirvana. It was a fresh, raw and vibrant print medium and sadly one that’s almost totally now gone.

Louise was a huge Charles Bukowski fan; the term “a good raping” littered his short stories and letters. Louise would use the term in conversation, as a lot of punk kids did at the time. I will explore the context later in the article.

Bukowski titles abounded in underground bookshops alongside previously-banned books likje William Burroughs’ “Naked Lunch” and Hubert Selby’s “Last Exit to Brooklyn”. Books and fanzines from the underground commonly used extreme terms and language. They carried stories of rape, S&M and so on, not necessarily endorsing those acts. The irony in what was going down for Louise was completely unnoticed.

Louise was a Doc Martin-wearing, pre-Riot Grrrll who hated (with a vengeance) prissy girls and prissy music. She was appalled by the stereotypes in music. Women should rock out on equal terms with men, she felt. She could not stand the bands that were pushing corporate girl-pop. Her heroes were Kim Gordon, Kim Deal, Babes in Toyland, Patti Smith and other women making tough, strong and loud music.

Yet, even in the context of the style of the magazine and as a Bukowski-like literary allusion, Louise’s line was completely ill-thought out and offensive. Yes, I imagine, it was also very hurtful.

“Lemon” was now accepting advertising from the big boys from the music industry. You could imagine the clueless marketing department saying: ‘Let’s get our band some street level cred; this fanzine could make our band cool’. There was an expectation that if you took advertisements you would not only review the record, but in fact give it a favorable review. Lou, however, was unaware that was how the Industry worked.

Louise Dickinson would have never played that game anyway.

In context, a positive “Lemon” review about another record opined: “I loved it as much as a public beheading of Jeff Kennett.” That could have been deemed an offence in a terrorism-spooked world in 2016. We see similar lines flash across social media every day of the week.

In context, a positive “Lemon” review about another record opined: “I loved it as much as a public beheading of Jeff Kennett.” That could have been deemed an offence in a terrorism-spooked world in 2016. We see similar lines flash across social media every day of the week.

The review pages in “Lemon” were called ‘The Music Police’. The real meat and potatoes of the fanzine were 1000-2000 words articles about bands. There were so many records reviewed - sometimes well over 150 an edition - that many of the critiques were never more than one or two sentences. A band would fortunate to receive four.

The reviews were by a variety of writers across Australia and could be abrasive, harsh and cruel at times. For example, just four words - “This is boring shit” – were devoted to Smog’s first album. In seeking writers for “Lemon”, Louise would state she wanted people who reviewed “in the Lester Bangs tradition”.

Louise was a huge fan of the underground American press and often talked about The Fanzine Shop in the East Village in NYC. While in the States, she was exposed to the tradition of radical magazines that started in in LA in the ‘60s. Where they would confront censorship laws, where they fought battles protected by the First Amendment.

The acoustic sugar pop duo Club Hoy should never have been reviewed in “Lemon”, to go one step further, that hurtful and offensive line never should have been published. Louise showed no understanding or sensitivity. Club Hoy were a hard-working, and dedicated band. What was to be gained by dissing musicians like this? They were also kids like Louise. The industry is hard enough and a struggle for any musician(s) with this sort of complete putdown. It was disappointing.

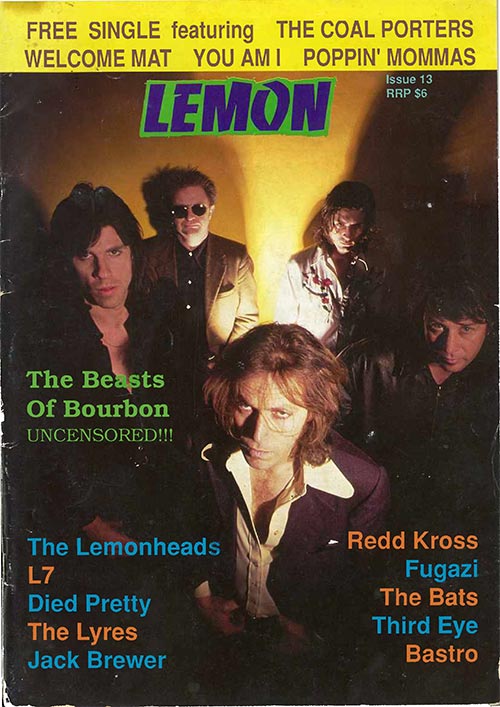

That said, “Lemon” was, and remains, one of the best and most exciting zines that the music underground of Australia has produced, emerging in 1987 until it folded after Louise’s suicide on May 24, 1995, aged 24.

Louise was 16-years-old when she started “Lemon”, attending gigs (underage) and all-ages shows. She would take her first edition around to shops by tram in Melbourne and sell them at gigs. Most of the bands featured were prominent in the indie scene at the time, like Hard-Ons, Died Pretty, GOD and Hellmen.

Also featured in those early editions were labels like Waterfront, Citadel, Au-go go and Phantom. Louise was one of the first to champion underground US labels such as SST, Sub Pop and Sympathy for The Record Industry.

It was in 1989 when Louise added a cassette to every edition. She saved money from each run to make the next one - with more pages and larger print runs. There were about four editions a year, usually in small runs of about 400-500.

It was in 1990, at age 18 and with her then-boyfriend, Cameron Craig, she headed to San Francisco and studied an Associated Diploma in music management and promotion for a year.

My own introduction with Louise was a sweet and kind letter sent from San Francisco, as she knew I was coming over to visit and stay. Cameron was a friend at the time; Louise listened to my band and sent a letter of praise. In her wonderful and charitable way, she also sent me a rare seven-inch of her favorite band, The Melvins.

Louise returned to Australia, and now had distribution for her magazine with US chain Tower Records. Eventually, she also found distribution in Japan. Her timing was perfect as “Lemon” hit a nerve just as underground, loud noisy rock became hip. Her magazine became a solid voice with a run of 2,000 copies and each issue featured a four-track, seven-inch single (which have now become very collectable.)

“Lemon” was a one-person production, with other volunteer writers across Australia. it was based in one room in a shared household.

Louise’s style of writing dramatically changed from the polite and humble beginnings of a schoolgirl to the later editions. From paragraphs of moving prose, dramatically shifting to self-loathing, arrogance and complete disdain for certain bands. The last editions had her falling between her usual love of certain bands to playing the victim, positioned as a druggie outlaw on the edge of life.

It appeared the success of magazine and the exposure to underground writers had made an impact. There was a sense of her writing being like an un-sanitised diary, as we entered her life of bad flat-mates and ugly neighbors and her fights against “uncool” people

Adrian Bull was in his mid- teens when he was first introduced to “Lemon”. Adrian managed independent record shops, and is one of the unsung heroes of Australian alternative music with more than a hundred releases under his belt as label head of Blind Records. He has sold more than 150,000 albums and CDs over the last 20 years. He saw Louise as a hero of the underground scene.

As a teenager obsessed with the indie/punk/fanzine community, finding “Lemon” was crucial. A magazine right at eye level. From ordering it through the mail to meeting Louise at shows and shooting the shit, it was a zine that inspired me to start my own (and later a record label).

Honest, to the point and bullshit-free... and put out by a woman in such a male dominated scene. Such a brave and inspiring woman. While our musical tastes varied a LOT (and boy could we argue about that) here was a vital piece of reading put out by a girl you'd be happy to have a beer spilt on you by. Louise knew how to tell it like is was through “Lemon”. She was just a couple of years older, so a peer', but I can guarantee you I wasn't the only music/zone obsessed teen from the suburbs that she inspired.

At the same time as "Lemon" was becoming popular, there was a uncontrollable tidal wave of opinion that was defining the underground, and sections of alternative music were becoming politically correct, prissy and quite sugar-laced.

At the same time as "Lemon" was becoming popular, there was a uncontrollable tidal wave of opinion that was defining the underground, and sections of alternative music were becoming politically correct, prissy and quite sugar-laced.

As the Australian music industry and its alternative music alter ego became more and more sanitized (as opposed to a a scene that was once so divided), it was all suddenly becoming quite simple: There was the mainstream and there was the underground, and never would the two worlds meet.

During the late ‘80s, a professional elite emerged in in the Australian Music Industry. These were people who ran booking agents, put on festivals, had labels, worked in the street press, worked on magazines, opersated inside PR companies and created close networks. Worse still, in the early ‘90s, professional government-funded lobby groups emerged.

As the underground, or “alternative” music was pushed into the mainstream, local acts like Ratcat hit number-one on the mainstream charts. With the commercial success of The Cruel Sea and Nirvana - and to the sound of Kurt Cobain hollowing “Rape Me” on his last album. - people smelt dollars to be made from street music. The scene eventually became lopsided with more middle-men and “industry types” hanging around on the fringes than musicians and songwriters making music.

Adrian Bull was working at Phantom Records at the time; and eventually became manager of Phantom's retail operation:

Around the time I started in music retail was just after the whole furore with ‘that review’ in ‘Lemon’. Funnily enough, the store where I started working was where I had bought that issue. We actually had a stack of copies out back and were instructed not to sell them and to wait for Louise to pick them up.

NOBODY agreed or thought for a single second that Louise was remotely serious with what she had (stupidly) said. That was how Louise spoke. She'd call her best friend a cunt. Louise was opinionated. Not necessarily loud in volume but loud in the way she spoke through her 'zine. Yes, HER zine, HER opinion. HER voice.

I was kind of young and full of the devil myself and did struggle with the double standard here. A small record store owned and staffed by staunchly independent minded folks who sure as hell knew how to say 'fuck you' rather than no comment. Who were we to censor this strong independent woman's right to her printed opinion?

Phantom refused to stock 'Lemon' while records by Neon Nazi racist band Skrewdriver, G G Allin (an artist who advocated raping teenage girls), and singles by noise merchants, Rapeman were sold.

In an article published in literary journal OVERLAND 2008 and reprimted online in Mess and Noise, Andrew Ramadge reflected:

A small piece appeared in a column in Sydney street magazine, Drum Media, reporting that Club Hoy was contemplating legal action over the comment. One week later, after he had been faxed a copy of the original review, a veteran journalist ran a larger piece, condemning the Club Hoy slap as 'a true low point in music journalism'.

It was not the last time the veteran journalist would write about the review, contrary to a statement he allegedly made to Dickinson. Louise had sent an apology for the Club Hoy review. Issue 16 of "Lemon" re-printed the response that Dickinson received on March 5:

Howdy Louise,

Thanks for the Fax, Just want to let you know you don’t get me wrong-I think LEMON is great, great mag (may it have a long live) I help the fact that I feel strongly that I can’t help the fact that I feel strongly that you properly inadverterbally (sp??) you over stepped the proverbial mark in that review, That the last you will hear/read from me about it. But boy was it a dumb thing to say !! Phew, just glad my fax jammed as I was about to send it to Stuart Littlemore (Media watch) Just kidding.

The matter did not go away. In Drum Media on March 16, the journalist reported he arrival of Louise's fax:

I was trying not to mention this again but the business about Club Hoy refuses to go die. It seems a well- known Industry organization wants to pursue the matter. There is talk that the review will be brought the attention of relevant television and radio shows - and even that approaches have been made to companies advertising in the magazine to with draw their support. The column has received a letter from the editor Louise Dickinson apologizing for the remark about the band’s new single.

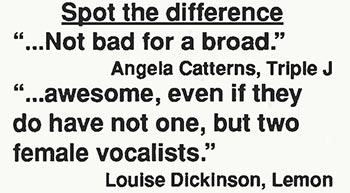

Louise was contacted by the writer for further comment and a full story he wrote appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald. In that article, Club Hoy and Kathy Bail, editor of the Australian edition of Rolling Stone, ripped her review apart, while Louise claimed that she knew her readership (a small fringe audience) and no one would have taken the remark seriously. Dickinson questioned why an the same level of outcry was not occurring against artists who advocated rape in their artwork and called for a boycott on Virgin Records over the forthcoming album by the rapper, Ice-T.

Issue 15 of “Lemon Magazine” had been in the stands for more than a month when Louise began receiving hate mail in her post box in Glebe. Amongst these letters was one from one of the heaviest hitters in the Australian music industry:

Your comments advocate violence towards women and are, therefore, totally reprehensible. They cannot be simply dismissed as a joke…We are collaborating with the Australian Women’s Contemporize Music Inc. in regard of this disgusting matter and alerting the music press and other music Industry what is a very serious matter.

Enclosed was a copy of another letter from him, sent to record labels Polydor, Phantom, Shock, Festival, Au-go-go, White, RooArt, Sony, MDS and ID. The letter urged them to stop advertising in “Lemon”.

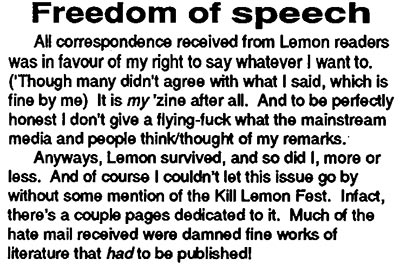

Triple Jay, the government-funded radio station that was heading into its own bland void as a homogenous "national youth network” now took sides. Dickinson later wrote in Issue 16 of “Lemon”:

Before I could even finish my breakfast cereal the hysteria began: I guess a lot of people read the Sydney Morning Herald article. Club Hoy and Vicki Gordon (Australian Contemporary Music inc) were interviewed on Triple Jay.

fAccording to Louise, an announcer declared: ”I know we must be an argument is about free speech. But freedom to say this sort of stuff. I don’t know about that.”

Triple Jay never bothered interviewing Louise. They never sought her side of the story. Eveb after their switchboard was alight with shocked listeners reacting to this one-sided account.

For Triple Jay to take this stand was odd. That station previously went out on a 24-hour strike over the song “Fuck the Police” by NWA, with staff staging a walk-out on the principle of freedom of speech. The same Triple Jay that was playing sexist gangsta rap, including an Ice T album with a rape scene on its cover.

Louise did indeed make a public apology to Club Hoy (her letter sent to Drum Media was mentioned in repoertage but never published.) Two weeks later, she rang Triple Jay and made a public apology on air. This is where it should have ended.

Drum Media’s rival, On the Street, joined in. A magazine with many times the readership of “Lemon”, it published a long letter from a reader stating:

I think you have serious mental issues Louise, you should seek psychiatric help as soon as possible …you should take a flying leap of the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Yes, what Louise had written was wrong, but this was the commercial street press publishing a letter advising her to suicide.

More was to come. Louise began receiving phone calls from tabloid TV:

'A Current Affair' were the first to ring: I could not believe it. What? 'A Current Affair' from the telly?. They wanted to interview me and I agreed. They were totally amazing. Then 'Today Tonight' called, this was really becoming really bizarre……..

As my phone disconnected the guy from the Today Tonight Show came to my house (how did he get my address) to see whether I would do an interview, he seemed be a decent guy, A bit of a wally; but that is O.K, He was trying to act young and swore a lot in effort to communicate with me.

Another TV program, “Real Life” contacted Louise, requesting an interview:

They took shots of me walking in and out of my house; I stayed inside, freaking out about the 'Today Tonight' people; I switched on Triple Jay and I was again in the lead news bulletin. They mentioned the Club Hoy thing again and said I could not be contacted. I was astounded. This was not news.

"Today Tonight" and "A Current Affair" ran stories the following day in prime time.

After these events, the hate mail dramatically increased.

There is no doubt that Louise presented a brave face and justified her (dubious) actions as the right to freedom of speech. There were so many arrows directed at her; coming from so many directions. Some of these arrows must have whizzed through her armour and pieced her.

In 2016 we are much more aware of the damage that bullying can do. The way Louise was bullied was an overwhelmingly one–sided use of power against an individual.

Louise’s editorial in Issue 16 characterised the critics as: The bastards who want kick the life out you.

Now, I am not suggesting the Club Hoy incident directly led to Louise’s demise but it certainly can be argued that it was a contributor to a downhill slide. Friends confimred that Louise had long-term mental health issues. Many of the attacks were not against the magazine; they were directed to Louise Dickinson personally. Lou sadly went down the road of substance abuse and her mother was diagnosed with cancer. Louise’s mother eventually passed away. Louise took her own life two weeks later.

Ed Jonker was in the music Industry at the time, as an advisor and industry writer. He is the founder of AIR (Australian Independent Records):

I’m familiar with ‘Lemon’, the fanzine she produced. As a music industry specialist with various Government organizations (Australian Trade Commission, Broadcasting Tribunal), as well as Project Manager for Triple J, I found fanzines such as ‘Lemon’ a useful source of information about developments at the grass roots level of the industry.

I remember the Club Hoy review and felt that the remark made by Louise was over the top, but took it to be part of her provocative style, rather than in any literal, malicious sense. I would have thought that a public explanation and apology to the girls in Club Hoy would have been the end of the matter and I was shocked to hear that Louise had taken her life.

Adrian Bull reflects:

No rational human actually condones rape. Just like now, but also rational humans should not condone a witch hunt. What Louise wrote was damn stupid, she was a kid, but haven't we all been young and said stupid things? Hell, I still say stupid things well in to my 40's.

Remember also - she publicly apologised. Not once, but twice. No person, let alone such a vital cog in our burgeoning music scene, deserved to be as publicly vilified as Louise was. The shameful double standards of the people.

It was not all one sided: there were letters of support from fanzine writers, and editors of underground music papers. Underworld editor David Higgins, himself a former “Lemon” writer who would go on to captain the flagship websites of both Fairfax and News Limited a decade later, wrote:

Louise’s achievements in promoting Australian music to the world far outweigh an offhand remark that served as fodder for sensation.

The last issues of “Lemon” were free; they were photocopied with limited advertising. I suppose Louise decided if she couldn’t sell it, she’d give it away at gigs. As mentioned, the writing was now wild, out of control, completely Bukowski-like, and Louise was now painting herself as the complete outsider, calling it her publication the “Lemonwankzine”

Louise was a talented writer. If anyone can get their hands on issue 14, it contained one of the most well researched exposes on the Australian Music Industry (“Music, Money and Lawyers”.) It was an examination of the cash-in on alternative and underground music by the major labels. Lou called it as she saw it. The piece is more than 12,000 words. It was intelligent and gutsy. And brilliantly written.

I will leave the last words to Andrew Ramadge and his powerful article in literary magazine “Overland”:

Something has been lost in music journalism’s move online. Much of the spark has faded, with criticism on the web too often falling into bland and uncritical fandom or tiresome attempts to legitimize pop music as a form of high art. Just how safe the ground these efforts tread becomes apparent when flicking through old copies of ‘Lemon’.

Dickinson’s unmediated thoughts jump thrillingly off the page – the textual equivalent of brushing one’s hand over broken glass or trying to walk along an imaginary tightrope on the pavement without ‘falling over the edge’.

To those who knew Louise personally as a friend, not the character she portrayed in last years of her zine, we all agree that Louise was a sweet and often vulnerable, fragile person. She spoke with excitement about her first love, music, her love of her fanzine (which was part of her identity), her garden and her “rockin dog, Arlo”.

"Lemon" magazine represented another time when we had a viable underground, a vibrant street-level music scene and people like Louise...real individuals who were writing and living out their existence on the edge of the mainstream. R.I.P. Lou.

Edwin Garland was a friend of Louis Dickinson and wrote this piece for Mental Health Week.