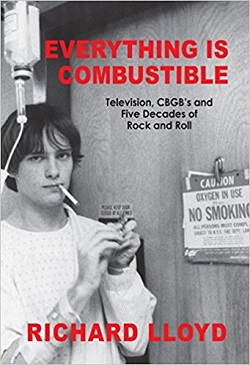

“Everything is Combustible” had me from a few pages in - and not just because I’m a Television fanatic. I consume music biographies like other people lap up those shitty reality TV cooking shows, but usually skip through the “formative years” to the chapters of glorious failure, the parts about career suicide and the stories about morbid squalor.

Lloyd confesses to the same impulse. There’s no time wasted in his book. He perfectly prepares you for what’s ahead, likening his own early life to that part of a rollercoaster ride where the chains are pulling the carriage up a climb to the first, anticipative summit. Once the rollercoaster is let go, it doesn’t stop.

Lloyd takes to the road in his late teens, trekking through the churning underbelly of late ’60s America like Jack Kerouac with better threads and a platinum blonde haircut. Of course he ends up in New York City and of course he runs rampant at Max’s Kansas City, embracing all its vices.

The crucial role of mercurial arts patron Terry Ork is outlined well; he’s not only the lynchpin for connecting Lloyd and Verlaine but ended up booking CBGB for much of its early period. He’s owed as much of a debt as bar owner Hill Kristal. By the time the NYC scene is about to awaken from its post-Dolls slumber, Lloyd’s own escalating drug use is a given. By the time of his serendipitous yet fated entry into Television, he’s already shooting up.

If you’ve been watching through the prism of digital media, you’d have seen the TV segments of Lloyd’s story have been well ventilated. His complicated relationship with the gifted yet lazy Verlaine is at the centre of Television’s career (or lack thereof) and if you’re a casual fan, there’ll be plenty new here for you.

The story behind the recording of Television’s masterwork, “Marquee Moon”, is engrossing. Lloyd’s own take on “Adventure”, the follow-up, is understandable because by that stage, he was being squeezed sideways by Verlaine – maybe with good reason given his rampant drug use. That part of the story is told without great rancour and the band’s demise is inevitable.

The band re-convened in 1991. Lloyd derides the resulting “Television” album as not being representative of the band. I fucking loved it but it does have the hallmarks of a Verlaine solo record with its close-mic’ed vocals and excursions into film noir. Lloyd makes it clear that he thinks Verlaine’s attitude killed any prospects of the band staying on a major label.

Lloyd stayed with Television until 2007 but bowed out, he says, when it was clear Verlaine had no interest in moving things forward. That’s his side of the story but you have to ask why a new, 10-track album reportedly remains in the can, lacking only Verlaine’s vocals.

There are oinly passing mentions of Rocket From The Tombs, who boasted Lloyd and Cheetah Chrome in the ranks (now, there's a pairing) in the '90s. Richard's riposte to Patti Smith, who he feels never treated him with respect, is a telling on-stage moment, related from his perspective. There's plenty said about the passing cast of Lower East Side punk scene characters, much of it magmanious.

Lloyd pulls no punches about his own major label career. His first post-TV solo work, “Alchemy”, is a gem, even with the keyboard trimmings added without his consent – but drugs derailed his career. Every album since then has had something to recommend it but the door to wider success stayed firmly closed. If you’ve ever heard Matthew Sweet’s “Girlfriend” record, you’ll know Lloyd’s work. He’s been in other bands but he and the late Robert Quine added real fire to that record.

That sort of fire burns brightly right through “Everything is Combustible”. It’s a disarmingly candid and skilfully written memoir.

Orthodoxy is not the Richard Lloyd way, so this book was never going to be a straight-forward elucidation of the histories of his bands (“Just the facts”.) It’s a weirdly charged ride through the man’s life, using vivid snapshots and taking colourful detours, and it reverberates like his guitar playing.

Orthodoxy is not the Richard Lloyd way, so this book was never going to be a straight-forward elucidation of the histories of his bands (“Just the facts”.) It’s a weirdly charged ride through the man’s life, using vivid snapshots and taking colourful detours, and it reverberates like his guitar playing.