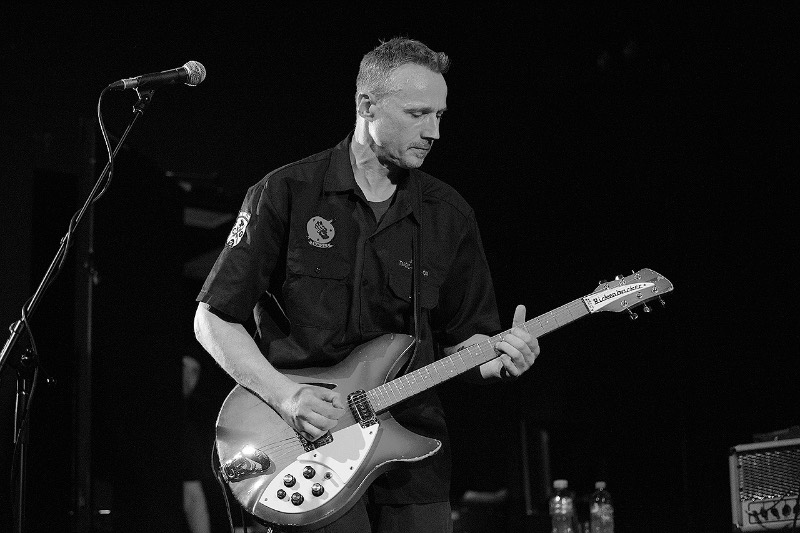

Kim Scott.

Kim Scott.

Formed in Adelaide in the early 1980s and based on the core membership of brothers John (guitar) and Kim Scott (bass), The Mark of Cain was always something of an enigma in the Adelaide, and Australian independent music scene.

The Mark of Cain took its initial musical cues from English post-punk bands like Joy Division and Gang of Four; the band’s muscular sound was complimented by a existentialist lyrical bent, inspired by John Scott’s interest in the writing of Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus and Herman Hesse, spliced with figurative militaristic imagery.

The fact that the Scott brothers, both qualified engineers, held down day jobs in the Department of Defence added to The Mark of Cain’s mystique.

John Scott.

John Scott.

After releasing two albums on Dominator Records in the 1980s, a chance encounter with Henry Rollins in early 1992 threatened to transform The Mark of Cain. Produced by Rollins, and released on the ill-fated pseudo-independent label RooArt in 1995, “Ill At Ease” nudged The Mark of Cain into the wings of popular awareness.

But, like its underlying thematic paradigm, The Mark of Cain was always going to stand alone in a crowd and, when RooArt was absorbed by Sony BMG, the band was pushed back into the shadows.

The Mark of Cain would go on to live another day, reforming periodically when the Scott brothers’ commitments permitted, But John Scott says, “Ill At Ease” was the time of The Mark of Cain.

After COVID-19 disrupted plans for a national tour to coincide with the 25th anniversary of the release of the album, The Mark of Cain has regrouped – delayed by Kim Scott’s injuries after a bike accident – to promote the first-ever vinyl release of “Ill At Ease” and a recording of the band’s set at the 1995 Livid Festival in Brisbane.

Patrick Emery spoke to John Scott about “Ill At Ease”, Henry Rollins’ love of The Mark of Cain and life’s perpetual existentialist dramas.

The first Iraq War started around August 1990. When did you and Kim come back from your respective middle-east postings?

I was there when the war started. I went over there in 1990. I was in Israel, Kim was in Alabama. I was in Tel Aviv. We came home in January 1991, I think. I was back in Adelaide for about six months, then went back there in May 1991 until May ‘92. It was pretty full on. I think maybe Kim hadn’t gone overseas yet, so we were able to do some shows while I was back.

Over what period were the songs on “Ill at Ease” written?

Some of them were written while I was overseas. I reckon I’d started playing around with “Contender”. I definitely did “Walk Away” over there, maybe even the beginnings of “Tell Me”. I had a four-track recorder that I missed around with, so I had a few things when I came back. I reckon “Tell Me” was one of the early ones we wrote together. I can remember teasing “Contender” out in 1992 or ‘93. We also did a lot of rehearsals, and sometimes Kim couldn’t make it, so sometimes it would be just me and Aaron jamming. I was playing bass and I came up with the “Interloper” riff.

By the time the album came out, The Mark of Cain had been playing for 10 years, you’d had a full-time job for a while and you’d be living and working in a war zone. Were the lyrics you were writing reflecting the life experience you’d had by that time?

Really, if anything, the lyrics are more of a metaphor for people dealing with shit in their lives, depression, even the whole existential idea of what the fuck is this all about? Some people just get up and they’re really happy to go to work and live their life. But I was attracted to these existentialist writers, like Sartre. That sounds very wanky, but I needed it because I was searching for answers.

When I used to read stories about World War I or the D-Day landings, trench warfare or Vietnam stories…it was people dealing with shit, day-by-day shit which is really bad. I’d never say my life just in getting up and going to work is like being a war – it’s not – but I got a lot out of reading stories about people who’d survived bad situations. I just liked the metaphor of it.

Some of it is interest in war. “Attrition”, from “Battlesick”, was pretty well written as an ode to the old poems of World War I, Sigfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen.

With “Ill At Ease”, even with the title you could use it as “stand at ease, boys”, or being ill at ease with the world. It’s a lot of metaphor. Even with “Point Man”, that translates to me as someone just doing things the way they think they need to do it – they’re out there, leading, and they don’t worry what other people are thinking.

With “Point Man”, and indeed other songs from The Mark of Cain canon, I’ve often wondered if there is a subliminal paradox – you have to almost forget about everyone else and the other extraneous matters around you, and just focus on what you’re doing in order to achieve greater outcomes for the group. Is that a paradox you’re conscious of?

Yeah, for sure, though I don’t know if it’s a paradox. One of the things I liked to read about in the Vietnam stuff was you’d have guys in the jungle dealing with shit, then someone would get shot, then “Don’t think about it, just drive on. Move on”. You can’t sit around and moan and complain – you’ve just got to live.

I really loved that idea – it was like the power of positive thinking, or whatever you want to call it.

With someone like myself, I’ve definitely struggled with depression, so you’ve got to find ways to push through. So I’m not sure on the paradox side of it – where that comes in is that you focus in on what you have to do and get it down.

There are points in my songs, like “Point Man” – “alone is the only way to be”. Well, no it’s not, it’s better to be with someone. But that’s a point in time when it’s like “Fuck that, fuck off everyone, I’m better off alone”. That’s a point in time.

I saw an interview with a guy who was in the Hotel Hanoi and he just had to basically deal with life. He was downed in about 1966 and didn’t get back to his family until 1972. They had their own way of dealing with things. In the morning they’d have smiling exercises because they’d noticed everyone was starting to get a droop around their mouths because they were so unhappy! I thought that was really interesting about how that guy got through. And if you can’t get through day by day, go and get some therapy.

I remember seeing The Mark of Cain supporting the Rollins Band, and I think Free Moving Curtis was on the bill as well, at The Old Lion in Adelaide in early 1992. Was that the first time you met Henry Rollins?

I’d spoken to him previously at a show when the Rollins Band came through Adelaide in about 1988, but I doubt he remembered me. When we played that night at the Old Lion, I remember when we got to the end of our set, everybody from the Rollins Band had come to the side of the stage – Sim Cain, Chris Haskett, Simon White and Henry were all there watching. And as finished and we walked off stage, they were all saying “That was great, great fucking show”, which I thought was very kind, but maybe they did that for everyone.

But after the show Rollins came out and said “Normally I’m doing all my push ups and exercises before the show but I could hear all this music and I had to come out and watch you guys. I can tell you that rarely happens. We’ve played with hundreds of bands this year and it’s rare there’s something of interest that we watch. But you guys were great – can I have a record?”

We gave him a copy of “Battlesick” and a few months later when he got back from tour, he unpacked his stuff and put it on and rang up (promoter) Tim Pittman and said “Can you get in contact with these guys – I want to put them out on my label.” That was one of those happenstance things – he really dug us.

What was it that Rollins liked about The Mark of Cain?

I think just the stripped down angularity of the music. Maybe even the muscularity of the music. He said the lyrics really spoke to him. And that made sense, because the books that I read, when he was producing “Ill at Ease” we were talking and he’d be saying “Yeah, I read that, I read that”. There was a lot of common authors that we read, even films that were our go-to touchstones. It was weird – there was this correlation, ‘I get where you guys are coming from’.

What was he like to work with in the studio?

He was really easy to work with, strong, definite ideas. Just know what we were going for, which was helpful for me. The only faith I had in myself was the faith in myself. I’d go into the studio and think “Fuck, man, I’ve got to sing in front of Henry Rollins”.

One time he pulled me aside and said “You’ve got a really great voice, you’re great, don’t doubt yourself, just go in and do it”. That was so great, and I don’t think he was just blowing smoke up my arse. I took it as a credible complement, and it made me feel really relaxed and I could be who I wanted to be in front of this person for whom I had great respect and awe. And he was easy to talk to, easy to work with. It was like personal spoken word for two weeks!

Did Rollins try and tour organise any tours for you in the US?

No, I don’t think we ever reached out for that. I think there might have been some talk of it at some stage. But one of the issues is that, at that point, trying to tour and make money and whether we were going to spend money and make nothing. It was one of those things that I think it would have been good to go overseas at some stage but nothing really transpired from all of that. That’s something that’s gone by the way, and we probably won’t ever play overseas, which is a pity.

You then ended up signing with RooArt in Australia, which was one of the first major label indie offshoots of the early 1990s. How did that come about?

That was through Nick Tallick, who knew the guy who was managing us at the time. Nick came to us and said “You and RooArt would be really good”, and we ended up signing with RooArt. Then RooArt ended up getting absorbed into that Sony BMG machine, so we were on Sony BMG for about a minute until they realised we weren’t going to make any money.

At that point we were introduced to Ian Dickinson, who’d just come over to Australia to run that arm of Sony BMG, and of course he went on to become ever more famous than anyone as “Dicko” on “Australian Idol”.

That was exciting times because when you’re on a major label they do treat you well, all your media gets set up so well. But we weren’t like a Screaming Jets or The Angels, generating a lot of income, so eventually we were dropped.

There was a period of time when The Mark of Cain had a significant level of national coverage – you played Livid in 1995, you played on the ABC’s “Recovery” music television program – that you’d never previously experienced. But you and Kim still had “real jobs”. Was there ever a time when you and Kim thought you could pursue music full time?

No, I don’t think so … it might have crossed my mind at one point. But it was never sustainable and I always saw that it wasn’t sustainable. We don’t write Top 40 music that appeals to everyone. Unless we did a real change in style and aimed to be more palatable, I didn’t see it. I was always happy that I had a job to fall back on, to be quite honest. It was good that I listened to Mum and Dad, even though I didn’t agree with them at the time!

Was it good having music as a release from your day job?

Definitely. I’d go to work, and I was in other bands as well, and I’d be practicing three or four times a week with The Mark of Cain or other bands. It was good. You were young and you had the energy. The Mark of Cain had a good run – the early 1990s was our time and then things move on. I like to think we were rather graceful about it. If people want to see us, they’ll come and see us when we play, but we don’t chase it.

When you listen to and play the songs you wrote back then, does it take you back to the time when you wrote the songs or do you transpose them to where you are now?

Probably not particularly. We rehearsed today and we played “LMA” and I was thinking of the actual girl it was written about, it was back in the 1990s, that did take me back. But otherwise not so much.

There are artists who don’t want to revisit older material because they cringe what they wrote when they were younger. Are you ever reluctant to play older material?

No, if anything it’s harder to work out what to play in an hour from the four or five albums. We often play 60 or 70 percent of “Ill At Ease” anyway – there will always be “LMA”, “First Time”, “Point Man”, “Contender”, “Interloper”, so there’s at least five of those songs. There’s lots of songs that we don’t play that I wish we did, but we’d have to learn them again [laughs].

“Ill At Ease” is still the time of us. Even though we did other stuff after [drummer] John Stanier joined, “Ill At Ease” is a real standalone sort of album that captures what I was thinking of, not to wank it up too much, but idea of the outsider, the existentialist idea of being alone, how you get through this life, how do you deal with it, what does it all mean. Sometimes you just have to suck it up and drive on and get through it.

That’s what it all illustrates – plus I was going through a split up with my wife at the time, so there’s a few things there, like “Remember Me” is about that, even “Interloper” is about people getting involved in shit that they shouldn’t. It’s very much a signifier of that 1993,1994, 1995 period of my life, so my early 30s.

I remember the first time I heard “Interloper” was this brief period when Lennie’s Tavern in Glenelg, which was basically just a suburban meat market nightclub, was hosting independent bands on Thursday night, and you could get in for free if you got there before 8.30pm. We walked into the band room and heard that bass line and I’ve never forgotten it.

That’s a punishing bass line in “Interloper”. Ha, yeah I remember Lennie’s. It was a very straight “pick up place”, if you know what I mean. The people who were there ordinarily wouldn’t have had a clue about the bands who were playing in the band room. They’d be wanting to hear Cold Chisel! And how they’re older people who got into Triple J and think that Triple J is the shit!

I remember when I was at school and a friend of mine and I were the only ones who were listening to the Sex Pistols and we were told what shit music taste we had, and these guys were listening to Supertramp,America, god, the worst bands. Then 10 years later everyone’s saying, “Yeah, I was into the Pistols”. No you weren’t! [laughs]

How’s Kim faring after his bike accident?

He’s good. That was the whole thing about today’s band practice. Kim had had the pelvic brace he’s been wearing taken off on Thursday, and he had Friday off, so he said “Let’s see how things are going on Saturday”. That shows how hardcore he is!

He was a little bit stiff walking but standing and playing he was fine. We went through the whole set today, as well as what might be encore songs. We hadn’t played for six weeks, and the reason we got together today was just to test the waters and see if we would be match fit for the Adelaide show.

And unanimous decision was that it was good. We’ve got a few more practices to tidy up a few things, but we’re good to go.

The Mark of Cain Ill At Ease Tour 2023

OCT

Friday 27 – The Croxton Bandroom, Melbourne VIC

Saturday 28 - Hobart Uni Bar, Hobart TAS

NOV

Saturday 11 - Freo.Social, Fremantle WA

Saturday 25 – Hindley St Music Hall, Adelaide SA

DEC

Wednesday 13 – The Basement, Canberra ACT

Friday 15 – The Metro, Sydney NSW

Saturday 16– The Tivoli, Brisbane QLD

Tickets